Beechworth

Orientation

Beechworth is one of five GIs in the North East Victoria zone, along with Rutherglen, Glenrowan, King Valley, and Alpine Valleys. Beechworth is small and the planted area even smaller — only about 127 hectares are under vine (the same acreage as France’s hill of Hermitage). Beechworth stands out amongst its neighbors: it sits on a plateau ranging from 300-1000 meters above sea level, on the continental side of the Great Dividing Range. The other GIs in North East Victoria sit in river valleys at lower elevations, and despite Rutherglen’s reputation for fine fortifieds, none come close to the vaulted quality that Beechworth produces for table wines.

Beechworth is about a 3 hour drive northeast of Melbourne, and 40 minutes shy of the New South Wales border. It is an old gold-mining town, and is considered to be one of the best preserved ones: it has 32 vineyards listed with the Australian National Trust. It’s population is a meager 4,900 people. Despite the premium nature of the wines produced in Beechworth, it is not a glitzy wine region, replete with fancy tasting rooms and posh resorts. It’s very much a small town of farmers and artisans.

Geology

The Great Dividing Range formed when the continent collided with New Zealand and South America 300 million years ago while a part of Gondwanaland. Within the GDR, the Australian Alps were formed as Gondwanaland began to break apart about 180 million years ago. The Alps were a pre-existing plateau that was lifted thousands of feet during the breakup, and today are the highest peaks in Australia. It is this bio-region of the GDR, the Australian Alps, where the Alpine Valleys of Northeast Victoria take form and descend from.

Prior to the formation of the Australian Alps a volcanic intrusion created three rises of Devonian Granite, and formed the hillsides that make up the area of Beechworth. As most of Victoria at one time or another was underwater, sections of Beechworth are of marine origin having been lifted up and preserved in large cradles of granite. Not all marine derived soils are rich in active limestone. The Ordovician era deposits are mixtures of friable shale, mudstone, greywacke, and sandstone that are around 450 million years old.

The younger Alpine Valleys surround the plateau of Beechworth, but are of a very different origin. A majority of the plantings in the region are devoted to granite subsoils which, along with the altitude of the plateau, attracted many winegrowers to the area. The Beechworth plateau looks south and west to the Ovens and King River valleys. To the east Mt. Stanley rises to approximately 1100m before giving way to the Buckland, Kiewa, and Mitta Mitta River Valleys, and then out to the heights of Mt Kosciuszko before the land descends to the oyster coast. To the north, beyond Mt. Pilot, lies the Murray River basin. Small creeks and streams carve their way across the region, but there is no focused point of watershed or body of water.

Human History

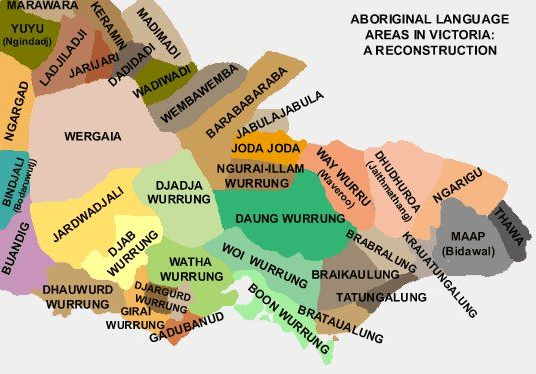

Beechworth, as we know it today, was originally referred to as Baarmutha by the Pallanganmiddang people Meaning land of many creeks Baarmutha is the traditional home of a people, like the other neighboring language groups and nations, that cared for and nurtured their country. The boundaries of different groups’ country were drawn by the many tributaries of the Murray River, and ran from the upper beginnings of these river valleys to the Murray River itself.

Waywurru is an exonym that applied to the Pallanganmiddang by the Kulin Nation, a union of the 5 nations that surround the bay to the south. The Yorta Yorta / Joda Joda Nation’s technical boundaries as prescribed by a 2006 Land Title Claim lie west of Beechworth, though the Bangerang people of the Yorta Yorta Nation have long been a part of the landscape of Beechworth. The Pallanganmiddang have yet to have an official Land Title Claim be adopted.

The mapped Dhudhuroa nation is also not legally recognized by the current Australian Gov’t (as insane as that sounds). The Barwidgee – a people most associated with the locale of Beechworth, and a group within the Pllanganmiddang Nation – spoke a dialect of Dhudhuroa. The Northeastern corner of Victoria, the Victorian Alps and its valleys have an unclear, and somewhat contested history. If only it weren’t erased through colonization.

The many tributaries of the Murray River along with sudden changes in landscape, namely elevation, create the natural borders of the these peoples’ country. Fisheries and races were constructed among various rock pools, burnings were prescribed to various parts and types of country to encourage holistic growth, planting yams or murunong, and the milling and grinding of grass seeds were all part of the Pallanganmiddang economy and broader way of Aboriginal life. Within the creeks, streams, and rivers that descend to the Murray, gold was often found and turned into ornaments and jewelry. It is estimated that the Pallanganmiddang population was somewhere between 800 and 1500 people by the beginning of the 19th century..

In 1824, Australian explorers Hume and Hovell trekked from Botany Bay in Sydney to the English and Swiss settlement of Geelong on Port Phillip Bay. On their 30 day journey, they crossed the Murray River where the Mitta Mitta meets it, and travelled southwest towards Geelong. They crossed Pallanganmiddang country, and recorded their observations of complex aquaculture and agriculture, and noted that the beauty of the pastures and woodlands looked as if they were a curated park. When they reached Geelong, word of the beautiful and fertile land they passed spread, and by the end of the 1830’s a small settlement was established in Beechworth and dubbed Mayday Hills after a place in England.

English settlers raised cattle and sheep, and planted wheat–as they have and will each time they claim a piece of land. In every iteration, sheep gravitate towards the grasses that foster the most life, because they are the most desirable. Once eaten, these grasses no longer exist to attract other animals, and the change up the food chain begins. Wheat is a highly invasive grass, and overtakes native grasses like Kangaroo grass, waddle, and other native oats that were turned into flour and cereals for winter sustenance. Conflict between the Pallanganmiddang people and the English settlers would only occur when land was being taken, or when the Pallanganmiddang would spear sheep as they would kangaroo; they have always hunted the game on their land, and they have only known that land as their home.

In 1851 gold was found in one of the creeks running through the region. Some of the early prospectors observed the large gold plates that Pallanganmiddang elders would wear around their neck, and recognized that there was a lot of gold to be found. A year later, 8,000 colonizers settled in the area in search of gold. One prospector noted that the area looked like “a grand park left to decay”. This, a result of the near disappearance of the Pallanganmiddang, as they were no longer able to care for their land. By 1857, 20,000 European colonizers settled in Beechworth to take part in the Australian goldrush.

Today, Beechworth is a well-preserved mining town. At the center of town, numerous buildings erected during the 1850’s stand today preserving much of what town was 170 years ago. The year-round population is less than 5,000 people, though the town swells to over 50,000 during peak tourist season. For the Pallanganmiddang and the Waywurru Nation, descendants still struggle to uncover a clear family lineage.

100% of Australia was inhabited by humans many thousands of years ago. In some cases, language groups, familial tribes and clans, and larger nations have preserved their culture through the telling of stories across generations, as it has always been done. The link of languages, and the different dialects within them are often the proof required to have the Australian government codify a people’s traditional ownership of country into law. However, in some cases, such lineage and history is not able to be proven to meet the standards of a colonial government, and, as in the case of the Pallanganmiddang/Waywurru, the Victorian Council of Aboriginal Heritage considered the Waywurru land title claim to be an extinct people.

The Pallanganmiddang/Waywurru spoke what is believed to be a dialect of the Dhudhuroa language. This language, in various dialects, is found throughout what is known today as Northeastern Victoria.ng As it stands today, the Dhudhuroa Waywurru Aboriginal Corporation, an entity needed to lay claim to traditional custodianship of a land, and the Murray Lower Darling Indigenous Nations Confederation (a non-profit that advocates for over 25 First Nations) are still fighting for acknowledgement of their country.

Wine History

Beechworth’s first vines are thought to have been planted by 1856 off Havelock road, one of the main thoroughfares leading east out of the city of Beechworth. The vine material was most likely sourced from the Adelaide Botanic gardens, and thus originally from James Busby’s cuttings. Unlike other areas that saw early vines, Beechworth actually made some well-regarded wine from them: the Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition of 1866-67 awarded an honorable mention to both an 1863 “Hermitage” and 1864 Chasselas from Beechworth.

This growth was a direct result of Beechworth’s gold rush, and as the community ballooned the interest in vine cultivation and urban development grew. In this time, Beechworth also had a brush with infamous outlaw Ned Kelly, who was imprisoned and tried in the township in the 1870s. Beechworth built up to having about 30 growers and 70 hectares in the early 1890s, but by 1916 only two hectares remained. Though there are no detailed accounts of why this decline occurred, it was most likely similar to what many Australian wine regions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were dealing with: devastation from phylloxera, economic depression, and a decreased export market as Britain’s imperial preference vanished upon Australian independence.

Though a vineyard was planted in Everton Hills (the western side of Beechworth) in the 1940s, it wasn’t until the late 1970s that a proper revival of the region was staged. Di and Pete Smith are credited with this feat, planting chardonnay and cabernet sauvignon on a 3.3-hectare plot just west of the township of Beechworth. Smith’s Vineyard is prized to this day, sourced by such notable producers as A. Rodda and Fighting Gully Road.

Rick Kinzbrunner followed soon after the Smiths, with his 1980 plantings near Everton Hills. His winery Giaconda has become one of the most acclaimed Australian wineries, putting the name Beechworth on the fine-wine map. Other early wineries include Elizabeth and Stephen Morris’s Pennyweight, planted in 1982 just south of the Beechworth township, and Barry and Jan Morey’s Sorrenberg, planted in 1984 just east of the city’s borders. These three wineries, still going strong today, built the foundation for many more to thrive.

The second generation to arrive in the 1990s, included Mark Walpole’s Fighting Gully Road, Keppel Smith’s Savaterre, and Julian Castagna’s eponymous Castagna. All three continue to be hugely influential to this day, and helped build up the banner of Beechworth, as well as aided with the GI-establishment (see Regions & Styles).

The new guard, arriving mainly post 2010, have only continued to build upon the legacy of these six producers. A. Rodda, Domenica, Sentio, Traviarti, Vignerons Schmölzer & Brown, Vinelea, and Weathercraft are all ones to watch.

Climate

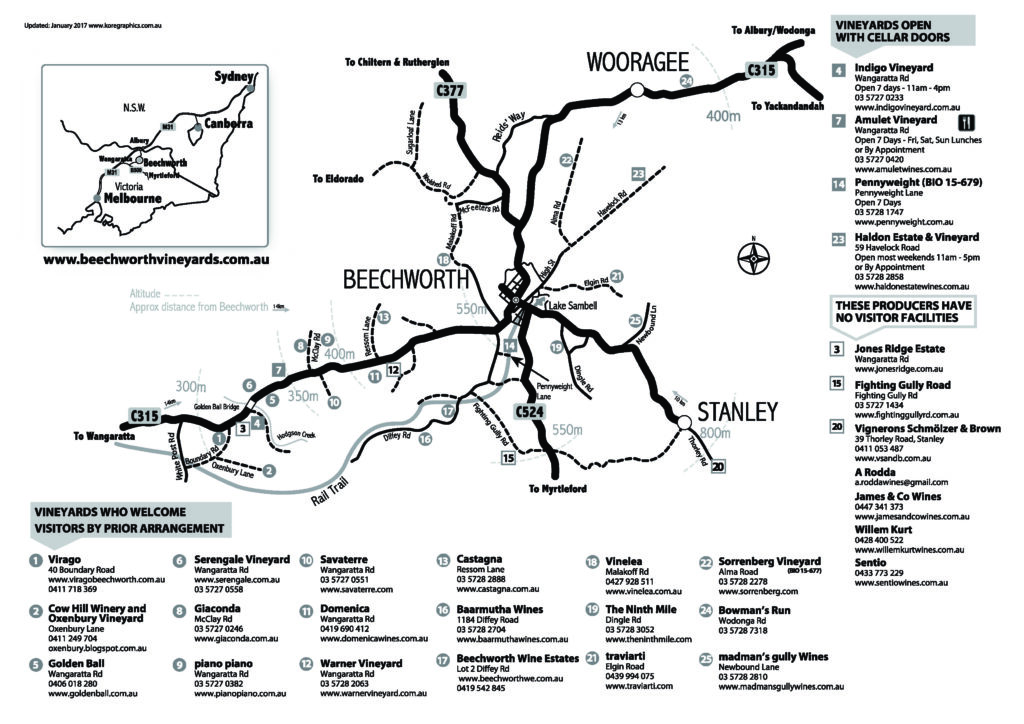

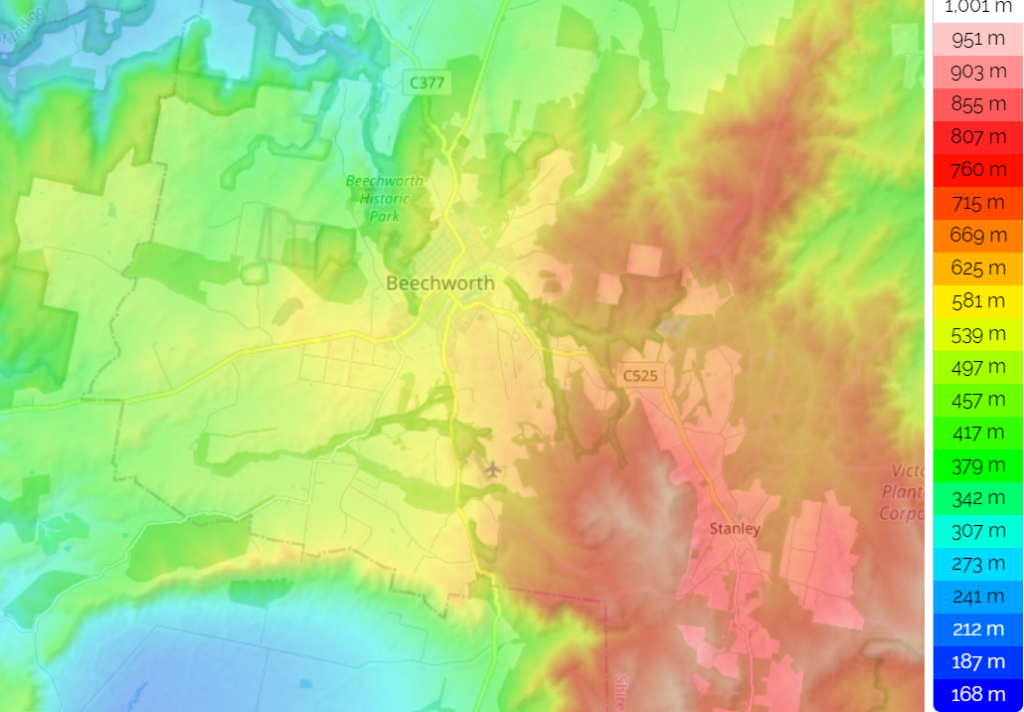

The plateau of Beechworth means that it overlooks a lot of warmer places. During the summer, the difference in temperature between the valley below near Wangaratta, and the lowest part of the plateau near Everton ranges from 3-5 degrees celsius. Head up to the town of Beechworth at 450m, and drop another 2 degrees. The vineyards at 800m are another 2 degrees cooler still. If there were ever subregions to be drawn, they would correspond with these climate zones – which are dictated by altitude.

The vineyards at and around 280m have about 1,725°C degree days – similar to the inland areas of central Italy. On the far northeastern edge near the town of Woragee just above 300m it cools down to about 1,687°C degree days, quite similar to Collio. The township of Beechworth proper, and the vineyards that rest around 500m experience a climate similar to Galicia with a heat summation index of 1,420°C degree days. And, the highest altitude plantings near Stanley (situated at 700-800 meters in elevation) have a heat summation of 1,240°C degree days, comparable to Tokaj, or Colmar. With these numbers, it’s easy to see why everything from riesling sagrantino can find a home in the region.

As elevation increases, so does rainfall. Plantings near Stanley seeing as much as 1200 millimeters per year, while lower elevation outcroppings can see less than 500 millimeters. Humidity also varies with elevation, with the highest spots experiencing the driest climate. At the center of the region, north of the town of Beechworth cold air can be trapped, and results in elevated frost risks, though using recaptured and recycled water in overhead sprayers could easily mitigate it.

The region is often photographed in a way that shows its vineyards perched above the clouds. Such a vantage point brings increased sunshine without the extreme warmth a lack of elevation would create. In 2020, the year recorded 3,621 sunshine hours, 100 hours more than California’s Palm Dessert, though not nearly as hot.

Beechworth Style

When Wine Australia set out to establish its GI system in the late 90s, minimum production criteria was set at 500 tons per harvest, and regions needed to contain at least 5 separate vineyards of at least 5ha each in size. Beechworth was too small to meet the requirements for an individual GI, and the bureaucrats wanted to include Beechworth in the greater King Valley GI or Alpine Valleys GI. Unlike those GIs, which had some mainly volume producers in control, Beechworth had small producers that were making big noise by producing wines of the highest quality. It was these producers that fought to prove that Beechworth was not like the valleys that appeared around it, and needed to be recognized as such. In 2000, the granite plateau of Beechworth was awarded its own GI.

In the modern era, fanfare around Beechworth’s ability to produce great wine is often focused on three grapes: chardonnay, shiraz, and pinot noir. Beechworth grows them very well, and in fact is home to one of the greatest chardonnay producers in the world in Giaconda (our humble opinion). Offerings from Beechworth are much more diverse, though, yet of the same high quality. Rhone varieties like viognier and roussanne thrive on its sunny granite slopes, and Italian grapes from sangiovese and nebbiolo to aglianico and fiano are huge successes in the older marine-derived soils. In the cooler, higher altitude areas riesling and other Teutonic grapes find success, as does pinot noir and gamay.

Beechworth has about the same area under vine as the Rhône Valley’s famed Hermitage, but can grow a cool-climate variety like riesling as well as it can a warm-climate grape like viognier. There are massive temperature shifts as one ascends from the 240m plantings in the southwestern corner of the appellation to the 800m plantings on the gentle slopes of Mt. Stanley in the east. As one climbs in altitude, the aspect of vineyards turns more northwest, giving way to warmth in an otherwise cold location. Most other vineyards slope softly south, and varieties are paired with a complimenting eastern or western orientation.

Zoomed-In

It is possible to think of Beechworth in three different subdivisions. These divisions are dictated by the climate created by their corresponding altitude, but also correspond to the various geological formations throughout the region.

As you move south toward Everton Hills, west of the township of Beechworth, granite becomes more common, with three granites that are unique to the region. The Golden Ball Adamelite formation is just north of Everton, is intertwined with the Everton Granodiorite, and confined to a section east of Wangaratta road. Here, ranging from 240- 350m in elevation, we find Domenica, Savaterre, Golden Ball, Weathercraft, and the Warner Vineyard. Across Wangaratta Road to the west lies the silicified zone of the Golden Ball formation, where large grey quartz deposits can be found. Elevation here runs up to about 450m, and Giaconda and Castagna have planted their vineyards at varying aspects to navigate the warmth of their area. Giaconda’s superlative chardonnay is planted about 50m lower in elevation than the shiraz for Castagna’s Genesis, but is in a much cooler spot thanks to its south eastern facing aspect.

This silicified zone continues northeast past the town of Beechworth and tops out at about 500m in elevation near Sorrenberg’s vineyards. Sorrenberg is known for its more moderate expressions of chardonnay and sauvignon blanc, crunchy gamay, and even utilizing the varied aspects to ripen an elegant expression of cabernet sauvignon. North of Sorrenberg approaching Reedy Creek there is a small bowl-shaped area created by younger glacial deposits during the Permian era. These are interesting outlier soils for Beechworth, but come with greater frost risk. Star Lane and Bowman’s run approach the frosty glacial soils, but lie on the outskirts, and haven’t reached the domestic appeal and critical acclaim as many others in the region.

The remaining area of Beechworth that lies east of the town, and rises in elevation as it approaches Mt. Stanley is where we find the older, marine derived soils of shale, mudstone, sandstone and greywacke. These soils are cradled and lifted by underlying granite intrusions, and the depth of the Ordovician soils ranges from 2m to 65m in some places. Directly east of the town of Beechworth we find Giaconda’s nebbiolo planting, Traviarti, Pennyweight, the Smith’s vineyard, and Fighting Gully Road as one approaches the southern edge of the plateau. All sit between 500-600m in elevation.

Lastly, continuing up towards the town of Stanley, is the exciting new frontier of Beechworth. Few plantings exist above 600m in elevation, making the Thorley Vineyard, planted by Jeremy Shmölzer and Tessa Brown, and the Brunnen Vineyard they manage, quite exciting. Shmölzer and Brown’s Thorley vineyard looks northwest, capturing sun and warmth needed for their 800m in altitude vineyard to thrive. While these plantings on Mt. Stanley may mark what’s next for Beechworth, there are still other pockets of Beechworth that are making growers curious. For a region that has achieved so much, there’s still much more potential on the horizon.

Beechworth's Future

There are only 32 growers in Beechworth, and it’s worth noting that 20% of them are certified biodynamic by either Demeter or NASAA. Sustainability has always been paramount, even before it was a good marketing tool.

Beechworth has few major concerns as a wine region, but bushfires are a big one. Only 7 tons of estate-grown fruit were reported to Wine Australia for the 2020 vintage (versus the 88 reported in the 2019 vintage)–and most of these 7 were probably for smoke-taint testing. Beechworth, Glenrowan, and Alpine Valleys were the only GIs in Victoria to be affected by the 2020 bushfires, but they were dramatically impacted, with outcomes ranging from fruit rejection, smoke taint expression, and outright loss. Many of the top producers in Beechworth announced in 2020 that they would not be producing any wine from the vintage. Just like on the west coast of the United States, bushfires have become a common occurrence in Australia, and Beechworth’s situation makes it particularly vulnerable to fires spreading down the Great Dividing Range from New South Wales.

Beechworth’s quality and diversity is renowned throughout Australia, but nearly invisible in the US market since the inception of the GI. A few producers have dipped their toes in, only to retreat in the face of fluctuating currency, the three-tier system, and a fickle market. Hopefully this is a region that we see more and more of in the United States in the years to come.

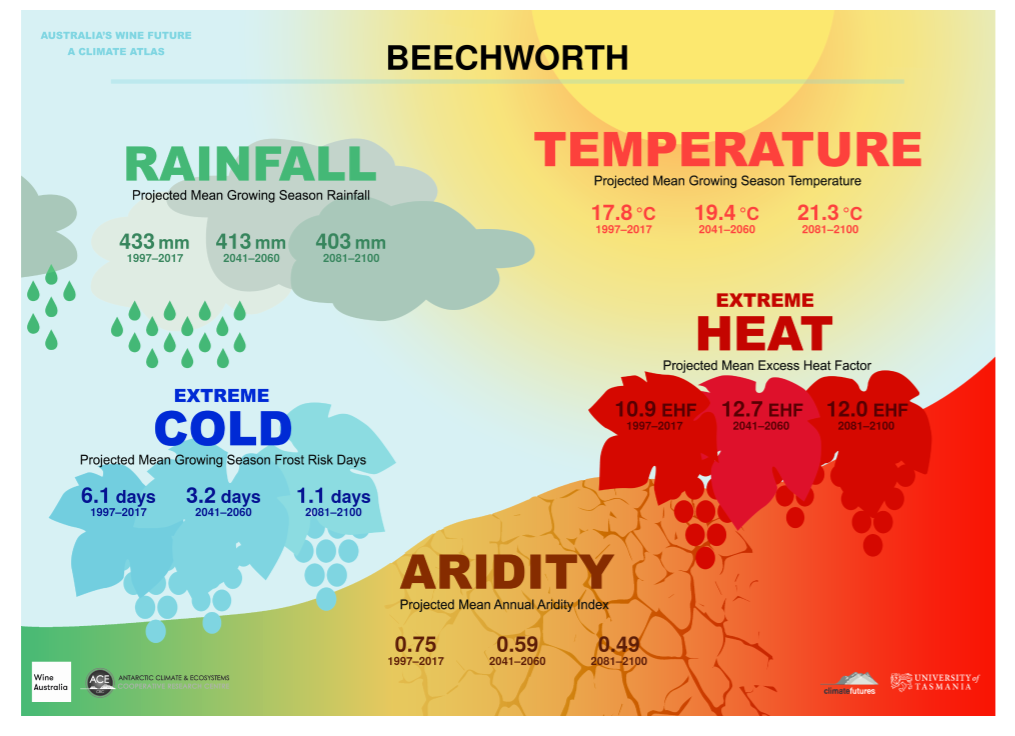

As Seen Through the Climate Atlas

The Climate Atlas is the culmination of a three-year study lead by the University of Tasmania, and analyzed 70 years of historical data across every Australian GI. Their predictions are based on this history, and present crucial metrics to understand what the next 80 years of climate change will bring to Australian viticulture and greater human life.

Notes & Definitions

- Growing Season is defined as the 6 month period from October 1st through April 30th, and is the time frame referenced by the Rainfall, Temperature, and Extreme Cold indexes.

- The Aridity Index uses an annual picture rather than the specific growing season within the year. It indicates the availability of water by measuring the accumulation of water against the evaporation of water, and represents the difference between the two. It does not take into account soil types, shading, changes in farming practices, or vine schematics (material, planting density, irrigation), but does take into account slope, aspect, elevation, humidity, and the effects of wind patters. There are few places in the world where rainfall is expected to increase at an equal to or higher rate than the increase in the rate of evaporation, so the entirety of Australia is expected to become increasingly more arid along with most of the world’s wine regions.

- Heat analysis and projections come with a high level of confidence across the climate analysis industry. Projections are linked to emissions models, and span a variety of well understood variables.

- The Extreme Heat Factor is used to measure the effects short-term intense heat experienced during heat waves have on humans. This factor is based on the three-day time period definition of a heat wave as it relates to the preceding 30-day temperatures of a specific place. Heat waves are large scale events that do not depend on specific regional details, and therefore the data relies more on overall climate change.