Tasmania

Orientation

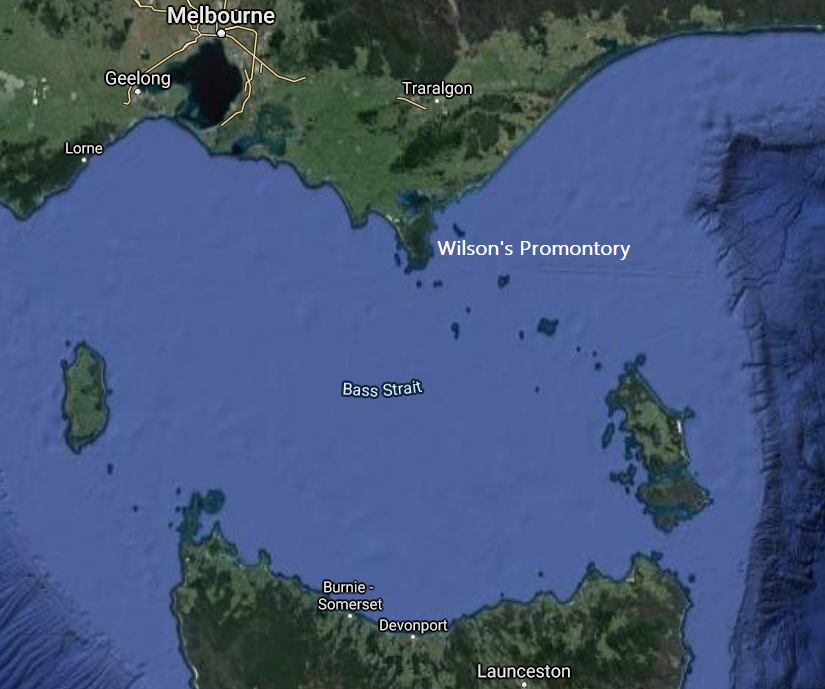

The island state of Tasmania is not only home to some of Australia’s top cool-climate wines, but is considered to be the country’s brightest viticultural future in terms of climate and financial investment. Just a 45-minute flight (or a 9hr ferry ride) from Melbourne, the main island of Tasmania is home to just over half a million people and accounts for 94% of the state, with the remaining land mass spread across over 300 small islands. The island squarely sits on the 42nd parallel, and coincidentally, 42% of its lands are protected as national parks or UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Hobart, its capital, is home to 50% of the population, and sits at the mouth of the Derwent River. Launceston, Tasmania’s second city, is home to approximately 20% of the population, and is about 45km inland from the northern shores along the Tamar River.

Tasmania’s entire production sits under one GI, Tasmania. This comes with both some positives and negatives. Fruit is expensive and hard to come by making it necessary for many Tasmanian wines to be a blend from multiple sub-regions. The wide breath of quality sparkling wines produced here is thanks to the assemblage of various sites across the island. A single GI allows for these producers to contribute to, and benefit from, brand Tasmania. However, this can mute the uniqueness of the different growing areas across Tasmania, keeping professional and consumer knowledge at the surface.

Geology

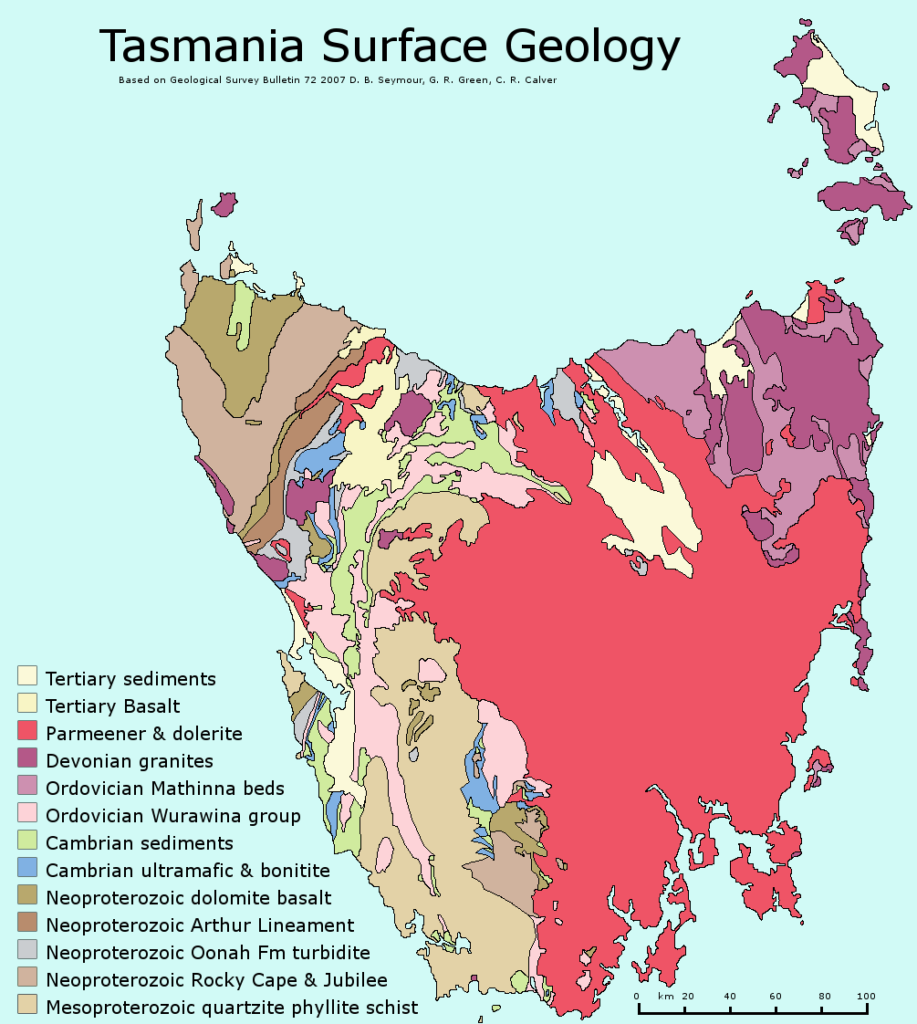

Tasmania has a deeply unique geological history that is different from the origins of the rest of Australia. Its oldest history dates from over 1.2 billion years ago, found in the form of metamorphic quartzite in the western portion of the island. This part of the island is now varied with multiple metamorphic formations of volcanic basalt, schist, and quartzite created between 400 million and 1 billion years ago.

The eastern half of the island is much more uniform: the world’s largest formation of dolerite, a micro-gabbro synonymous with volcanic basalt. Nearly all of Tasmania’s agricultural areas sit upon this bedrock aside from the north-eastern corner. This formation began during glacial conditions 300 million years ago and created what stands today as the Tasmanian Basin. Volcanic activity during the Jurassic period brought a massive magma intrusion creating a mountainous landscape and the dolerite bedrock upon which Tasmania’s vineyards grow. Sandstone and quartzite weave through beds of Devonian granite at Pipers River in the north and cap the north-eastern corner of the island, stopping just before Wine Glass Bay on the east coast.

Tasmania’s temperate rainforest-covered western coast is firmly isolated by a series of elevations, mountains, and highland plateaus that define the central western portion of the island. Notables like Mt. Ossa (1,600m), Mt. Field, Craddle Mountain (1,500m), Mt. Pelion (1,560m), the Du Cane Range (1,520m), and kunyani/Mount Wellington (1,260m) along with 50 others were all formed during the Jurassic intrusion creating a stark rain shadow effect in the east making all types of agriculture possible today.

History

The earliest humans to have arrived in Australia are thought to have come through Java in Indonesia and out of Africa by way of Asia. The Ice Age that spanned from about 2.6 million years ago to about 11,700 years ago resulted in very low sea levels creating numerous land links in what is today a sea of islands. Papua New Guinea was once connected to Australia where the Torres Strait now lies, and the Northern Territory is where humans first arrived in Australia 65,000 years ago.

The clear distinction between Australian Aboriginal First Nations and Torres Strait Islander First Nations acknowledges that the original inhabitants of the now scattered Torres Strait islands arrived thousands of years before humans descended further south into Australia. Archaeological proof shows us that much of the east coast of mainland Australia was wholly inhabited by humans nearly 50,000 years ago and soon thereafter the southern peninsula of the continent, Tasmania.

North-eastern Tasmania was joined by a land bridge to Wilson’s Promontory in Southern Victoria, and archaeological findings show us that there was a human settlement along the banks of the Jordan River near Hobart at least 42,000 years ago. The collection of fertile and safe estuaries, lagoons, and bays along the south-eastern corner of Tasmania drew the peninsula’s first settlers south, and this area remains the most densely populated area of the island today.

Fluctuations in temperature as the world neared the end of its last ice age resulted in the land bridge to Victoria becoming temporarily flooded around 36,000 years ago, giving Tasmania a preview of the island fate that would lie ahead. The climate cooled, and the land bridge returned about 6,000 years later, resulting in more people travelling further south. The next 12,000 years would result in growing settlements and populations all around Tasmania, and in particular the coast. Around 18,000 years ago, the Ice Age started to come to an end, resulting in a slow rise of the seas. Coastal cave settlements along the southwest started to dismantle, and by 12,000 years ago, with a fairly sudden and drastic tilt of the earth’s axis, the ice age came to an end, permanently turning Tasmania into the island it is today.

Wetter and warmer conditions continued, causing the rapid forestation of western Tasmania. Rivers rose, and long-established coastal settlements continued to flood. Around 8,000 years ago, controlled burning became a common tool to clear areas of forest for settlements (and to control wildfires). As sea levels and warming temperatures began to stabilize, settlements became more permanent. Rivers, estuaries, and lagoons became life sources. Tasmania supported a diverse diet of fish, birds, land mammals and plants.

By 3,000 years ago, nearly the entire island was occupied along with many of the smaller satellite islands. Regular controlled burnings occurred to reduce bush-fire risk, to cultivate grasslands for grazing animals, and to spur the growth of various plants that were a part of the human diet. This hybrid of agriculture and hunting/gathering was common for Aboriginal nations, an identity often lost to the history of the colonizers, which tells the story of the Europeans implementing agriculture themselves.

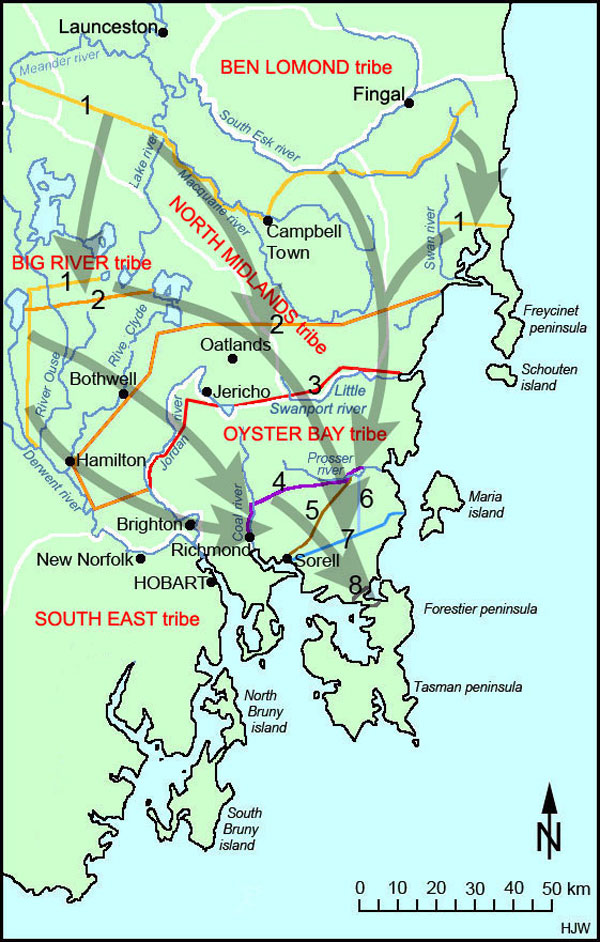

Much of the original history of Tasmania has been lost or rewritten. In other parts of Australia, the languages of the First Nations and Clans have been preserved. However, that is not the case for the First Nations of Tasmania. The western coast of the island was home to the Peerapper and Toogee Nations. Along the north, the Tommeginne, Tyerrenotepanner, and Pyemmairrener Nations, the east coast was Paredarerme country, and the coast south of today’s Hobart is the Nuenonne Nation. The Laimairrener Nation was the only one to not occupy any coastland. Between these eight nations, historians believe there were between 3,000 and 15,000 people living in Tasmania at the time of European “discovery”.

The terminal speaker of any of these first languages, Fanny Cochrane Smith, died in 1905 and with her much of the history of human life on Tasmania. Today, some 40 words remain and mainly describe notable places. The Tasmanian Aboriginal Center (est. 1970) preserved these words, and with the help of the remaining descendants of the First Nations, established the palawa kani (intentionally lower case) Aboriginal language. The palawan name for Tasmania is lutruwita; it is taken from language spoken by the Bruny Tribe whose traditional lands were the islands that were part of the Nuenonne Nation. Lutruwita, what the Bruny Island Tribe called the big island, was reconstructed by an Aboriginal linguistics professor, using both the mainland and island languages of the Nuenonne Nation.

Lutruwita was first sighted by Europeans in 1642 when Abel Tasman, sailing on behalf of the Dutch East India Company, spotted the fires of the Peerapper and Toogee Nations along the west coast. He dubbed the island Van Diemen’s Land for his governor before sailing onto the South Island of New Zealand. Upon his return to the Dutch outpost of Jakarta, word of the land south spread, spawning numerous European exploratory visits to Tasmania.

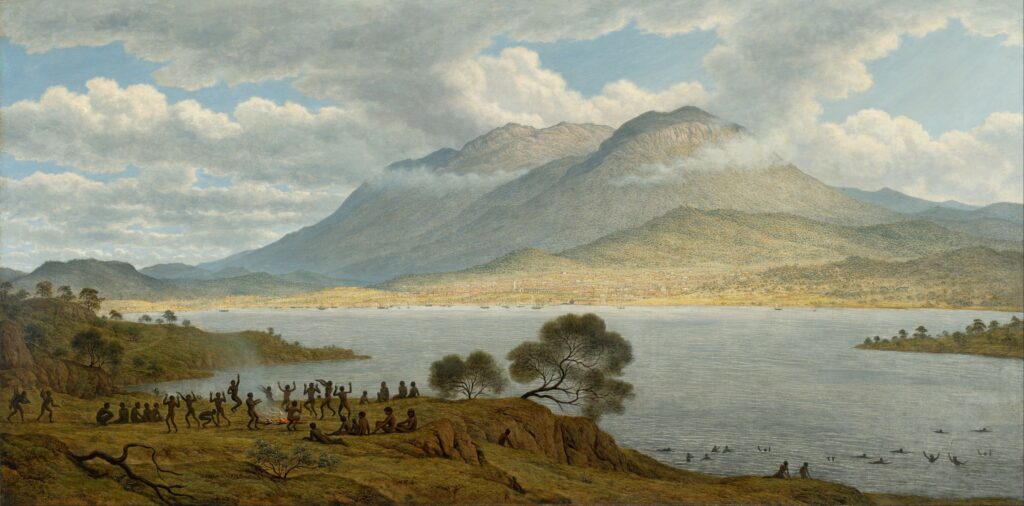

By the beginning of the 19th century there had been many French and English landfalls around lutruwita. Both friendly and hostile interactions between locals and the colonizers ensued. British forces travelled from Sydney to establish a colony on lutruwita, and landed along the Derwent River at piyura kitina, or known today as Risdon Cove. The clearing they deemed appropriate for settlement was the result of the local clan’s burn farming to allow for grazing animals to thrive (and be hunted). The English settlement occupying the traditional hunting ground of piyura kitina brought a level of (justified) outrage to the local clan, and several incidents of violence occurred between local Aboriginal people and the English. On May 3rd, 1804, a kangaroo hunting party of men, women and children arrived near the settlement. Alarmed, the English fired warning shots, and then a canon and musket rounds at the party. Witness accounts of the accurately named “Risdon Massacre” record anywhere from 5 to 50 Aboriginal deaths.

The following years brought an influx of colonisers, drought, disease, and increased waves of violence as the original settlers and the English competed for food. In many cases, free colonists and convict hunters were regularly abducting Aboriginal women and children while murdering men. From 1817 to 1828, nearly a million acres of Aboriginal hunting grounds throughout the north, central, and eastern portions of lutruwita were given free by government to invading colonists. In 1828, martial law was declared allowing the English to shoot locals on sight. This period of time was a true act of genocide, and is known as the “Black War”. In 1830, escalating his martial law proclamation, Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur ordered an offensive known as the “Black Line”, in which over 2000 English civilians and soldiers banded together as a series of waves that stretched hundreds of kilometres across the island. They marched, driving Aboriginal people from the settled districts of the island to the far southeast Tasman Peninsula.

Survivors of the war were exiled and imprisoned on

Flinders Island, where many died from respiratory diseases. Others who

had fled north established a community on Cape Barren Island (CBI) north

east of the main island. Through the end of the 1800’s, the Aboriginal

community lobbied for land rights and a school on CBI. A reserve was

established for Aboriginal Islanders and an Aboriginal Association was formed

to manage the main form of income for the community – muttonbirding (the

sustainable harvesting of seabirds for food, oil, and feathers). With the death

of Truganini in 1876, a woman believed to be the last full-blooded Aboriginal

Tasman, the myth of Aboriginal extinction became a reality.

This didn’t mark the end for the struggles of the Aboriginal people of lutruwita. Aboriginal graves were dug up and remains were stolen for profit. Just before WWI, the CBI Reserve Act limited citizenship rights for reserve residents. In the 1950’s, after a failed initiative to gain ownership of the reserve lands, the reserve was closed and welfare authorities forcibly removed children. It wasn’t until 1985, after years of petitioning, that the government legislated the return of all human remains sitting in museums to the Aboriginal community. In 1995, 3,800 hectares of land including Risdon Cove was returned to the Aboriginal community, and in 1997 Tasmania became the first state to formally apologize for the forced removal of children. Today, numerous culturally rich lands have been returned to the Aboriginal community, and in 2006, Tasmania became the first state to legislate compensation to the “Stolen Generations” and their families.

Tasmanian Wine History

Bartholomew Broughton, an Englishmen that served in the Royal Navy during the war of 1812, and then arrived in Tasmania as a convict, is responsible for planting Tasmania’s first commercially viable vineyard. His 1823 plantings in Newtown, just north of today’s Hobart city center, were not only Tasmania’s first, but Australia’s first, with wine from his 1826 harvest being sold in 1827. While Tasmania had over 40 different grape varieties planted by the mid 1860’s, it came to a screeching halt in the latter portion of the 19th century, as the gold rush on mainland Australia took form and interest in Tasmania dwindled.

The modern age of Tasmanian wine starts in the 1950’s with the establishment of two vineyards. Jean Miguet from Provence had arrived to work on a large hydro-electric plant through a government commission. He originally leased, and then purchased, his property just outside of the city of Launceston near the Tamar River. Known today as Providence Vineyards, it has changed hands numerous times though still celebrates its origin story today. The second vineyard was planted by Italian textile merchant Claudio Alcorso in 1958 on what is known today as Frying Pan Island. Today, the estate is called Moorilla and owned by Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) proprietor David Walsh. Alcorso’s affinity for the arts has reached uncharted heights with the merger of the winery and a world-renowned museum into one holistic experience.

Today Tasmania is a complex mix of big business vineyard ownership and small family-run estates, scattered across many unique growing areas that sit under the single GI of Tasmania. With land being too expensive, the model of micro-negociant, or hybrid negociant-grower, is quite prevalent, though many young winemakers are taking it upon themselves to plant and grow as well as make. As climate change becomes more drastic and volatile, Tasmania is experiencing its own “gold rush” as the cool climate growing region and access to water makes it highly attractive. The largest players include Treasury, Fogarty Wine Group, Accolade, Samuel Smith & Sons (Yalumba), and Brown Brothers.

Climate

There’s no shortage of celebration around Tasmania’s cool climate. Considering mainland Australia is nearly 35% desert, and only a small slice of the southern section is considered temperate, there’s reason to celebrate in Tasmania. There is plenty of elevation throughout the island, but most agriculture and viticulture takes place in lower lying river valleys. The topography of the island can reach over 1200 meters above sea level, and all vineyards are planted below 500 meters with most along river valley floors less than 200 meters above sea level.

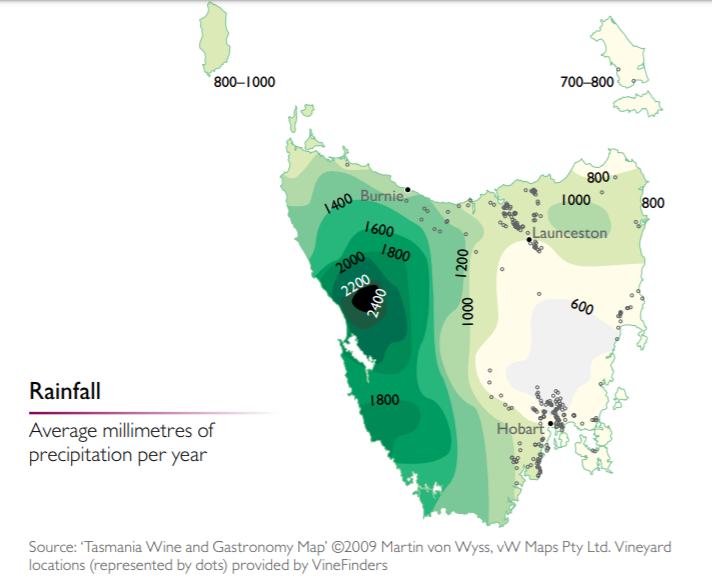

Tasmanian viticultural areas enjoy a lot of sunshine. In the northeast, near the Tamar River Valley, vineyards get an average of 2550 sunshine hours annually. As comparison, Burgundy sees about 1800 sunshine hours annually, but only varies a couple of degrees Fahrenheit in average temperatures. Rainfall in Tasmania is anything but uniform. The rain shadow effect in Tasmania is evident in extreme. The western portion is a dense temperate rainforest that receives weather flowing off of the Indian Ocean, crossing the Tasman Sea and Southern Ocean. Aside from a few coastal areas, it is not suitable for domesticated agriculture. Agriculture is abundant across the eastern portion of the island as it basks in a rain shadow. Dubbed “the Apple Isle”, it was once a major contributor to the world’s apple harvest. In the north, river valleys enjoy gentle rainfall that creeps south from the Bass Straight. The south is drier still, and in many places demands irrigation.

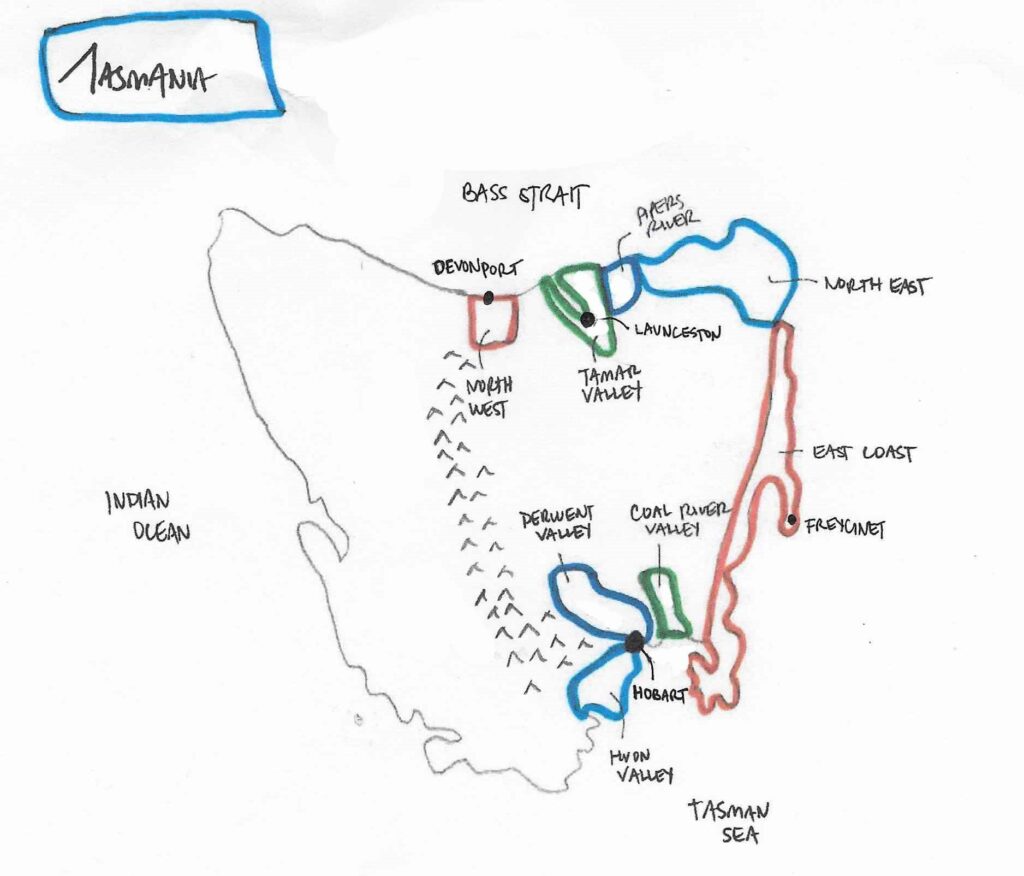

Regions

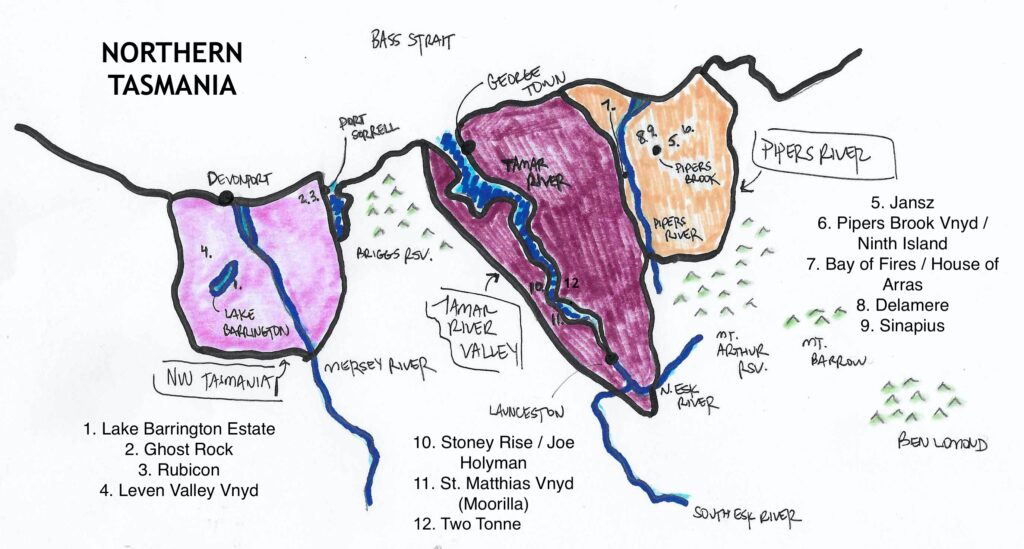

Tasmania can be grouped into a few larger zones that contain various subregions. The north coast is home to (west to east) the Northwest, Tamar River Valley, Pipers River, and the Northeast; the long stretch of the East Coast which extends 150k south from Freycinet to Boomer Bay; and the South East where the Huon, Derwent, and Coal River Valleys surround the greater Hobart area.

The Northwest subregion extends 45km west along the coast from Port Sorell and Devonport to Burnie, and extends inland in its eastern portion for about 30km from Devonport to Sheffield. The coastal and inland areas are quite different, with the inland area receiving 20% more rain than the costal areas during the peak rainfall months, and also being drier in dry months. The inland area also deals with greater temperature fluctuations with warmer highs and colder lows.

The Northwest has not achieved the critical acclaim or

commercial success of many other Tasmanian regions, but is nonetheless the source of some excellent wines. Notable producers here include Barrington Estate in the inland area, Ghost Rock and Rubicon Estate east of Devonport near Port Sorell, and the Leven Valley Vineyard further west. Production varies here with colder sites being well suited for the production of sparkling wines, and still wines being produced from sauvignon blanc, riesling, chardonnay, pinot gris,

and pinot noir. Bounty from the Northwest often finds itself blended with other sources as well.

Of Tasmania’s 1,702 hectares of vineyards, nearly 40% of them are located in the Tamar River Valley, though more producers are based in the neighboring Pipers River. The Tamar River itself is Australia’s longest tidal river (flow and level effected by changes in ocean tides). Its head is at the city of Launceston 65km upstream from where it empties into the Bass Straight, surrounded by wide sandy beaches. The valley’s inland borders are defined by the Tamar’s tributaries – the North and South Esk Rivers – and enjoys gentle rains that move in from the west. The land is rich and fertile, supporting a variety of agriculture beyond grape vines.

Elevation is not much of a thing here, and therefore less climate variation occurs as one moves inland. Vineyards along the interior, upper reaches of the Tamar rarely sit above 60m above sea level, and the tidal influence on the Tamar River speaks to the small altitude gains. The valley is framed by a few mountains, namely the Briggs Reserve in the lower western portion of the valley, and then three mountains, Mt, Barrow, Mt. Arthur, and Ben Lomond cradle the eastern interior retaining moisture that travels up the river valley from the coast.

Launceston, or Launnie as one from Tassie would call it, sits on the 41.5th parallel, and the growing region enjoys a climate quite similar to Burgundy. Pinot noir is the most planted grape in Tasmania, and that holds true in the Tamar, with chardonnay and riesling in abundance and other varieties like gewürztraminer, grüner veltliner, gamay, pinot gris, and sauvignon blanc all planted. Sparkling has long been associated with Tasmania, and the most prolific sparklers all originated in the Tamar.

The Tamar and Pipers Valleys are often grouped together depending on which appellation is thought to be more marketable at the time, and the lack of official GIs only exacerbates this issue. The Pipers River is narrower than the Tamar River, and coupled with more elevation (vineyards up to 270m), there is greater frost risk. Both regions deal with a good amount of disease pressure from moisture, but selecting north and east facing slopes for vineyards is the first and most important step in managing both disease and frost.

Generally, the Tamar is warmer, picked about two weeks earlier than Pipers River. Where the Tamar skilfully crafts pure still wines, Pipers River is as focused as ever on sparkling wines. Producers like Jansz, named for Abel Tasman’s middle name Janszoon, planted their first vineyard in the Tamar as its proximity to the city of Launceston was favorable. However, larger producers like Jansz along with Pipers Brook, Bay of Fires, Arras, Ninth Island and Delamere all focus on sparkling wines from Pipers River, but produce still wines grown throughout the north including the Tamar under their Pipers River banners. Moorilla’s St. Matthias vineyard provides grapes for their still and sparkling wines from Tamar. And younger producers like Joe Holyman’s Stoney Rise, the late Vaughn Dell’s Sinapius, and Ricky Evans’ Two Tonne have shown how bright the future is for Tamar and Pipers River Valley still wines.

East of the Pipers River Valley lies more of Tasmania’s cool temperate rainforest. When speaking of wine regions, this area is sometimes referred to as the Northeast, but often times just skipped over altogether in viticulture conversations. There are small areas of farmland dotted along the north coast where rain fall diminishes slightly. The thickest parts of the northeast rainforest extend outward from Ben Lomond through a series of reserves stretching to the east coast at Coles Bay. Viticulture has certainly been tested here, but the high moisture brings with it serious disease pressures.

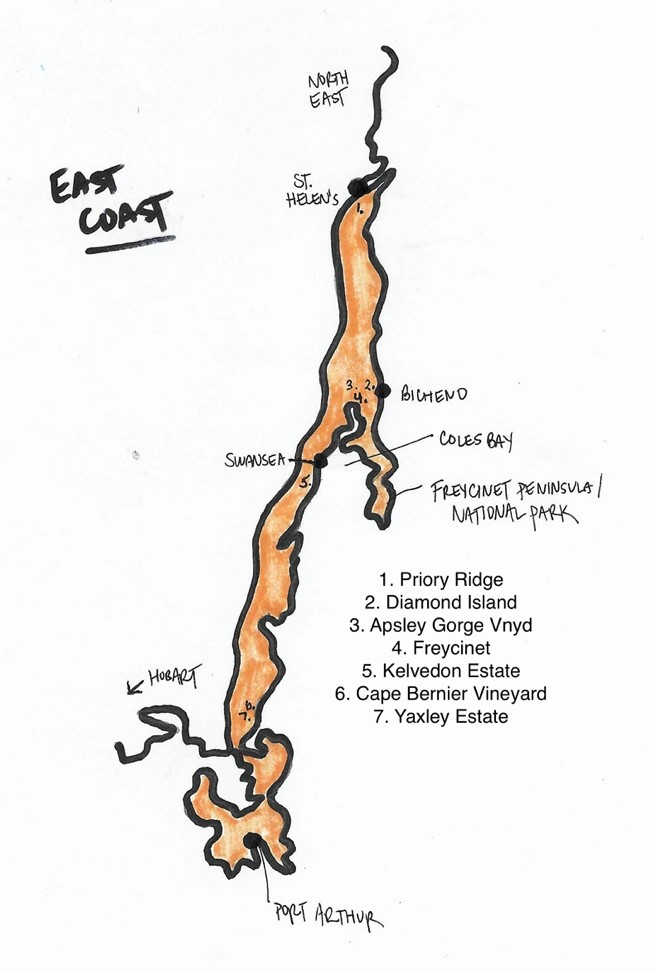

The vineyards of the East Coast have historically been sparse, but it is one of the focal points for rapid planting and industry growth; the current vineyards and estates don’t have much in the way of market share or critical acclaim, but that has the potential to change. The East Coast is the warmest wine growing region of Tasmania, often a couple degrees Celsius warmer than Hobart. It also receives about 12% more rain annually. The East Coast can be separated into upper and lower sections, though differences in climate and topography are negligible. The Upper East Coast extends from Coles Bay and the Freycinet Peninsula north along the coast through the town of Bicheno. The settlements around the Freycinet Peninsula began as sealing and whaling outposts, cues taken from Aboriginal clans that originally lived there.

A few isolated wineries are located north of Freycinet: Priory Ridge (the furthest North), Diamond Island, and Apsley Gorge. In 1980, Freycinet became the first winery to open on the East Coast, and visitors enjoy the bounty of rich local agriculture and fishing. Pinot noir is the most abundant grape here, and the East Coast produces the fullest and ripest examples. Kelvedon Estate at Swansea located along the inland coast of Coles Bay marks the southern end of the Upper East Coast. The Lower East Coast is a bit younger, and has yet to reach the tourism heights of the areas of Freycinet. Cape Bernier Vineyard and Yaxley Estate mark the reaches of the southern end, without established viticulture further afoot on the peninsulas and Port Arthur.

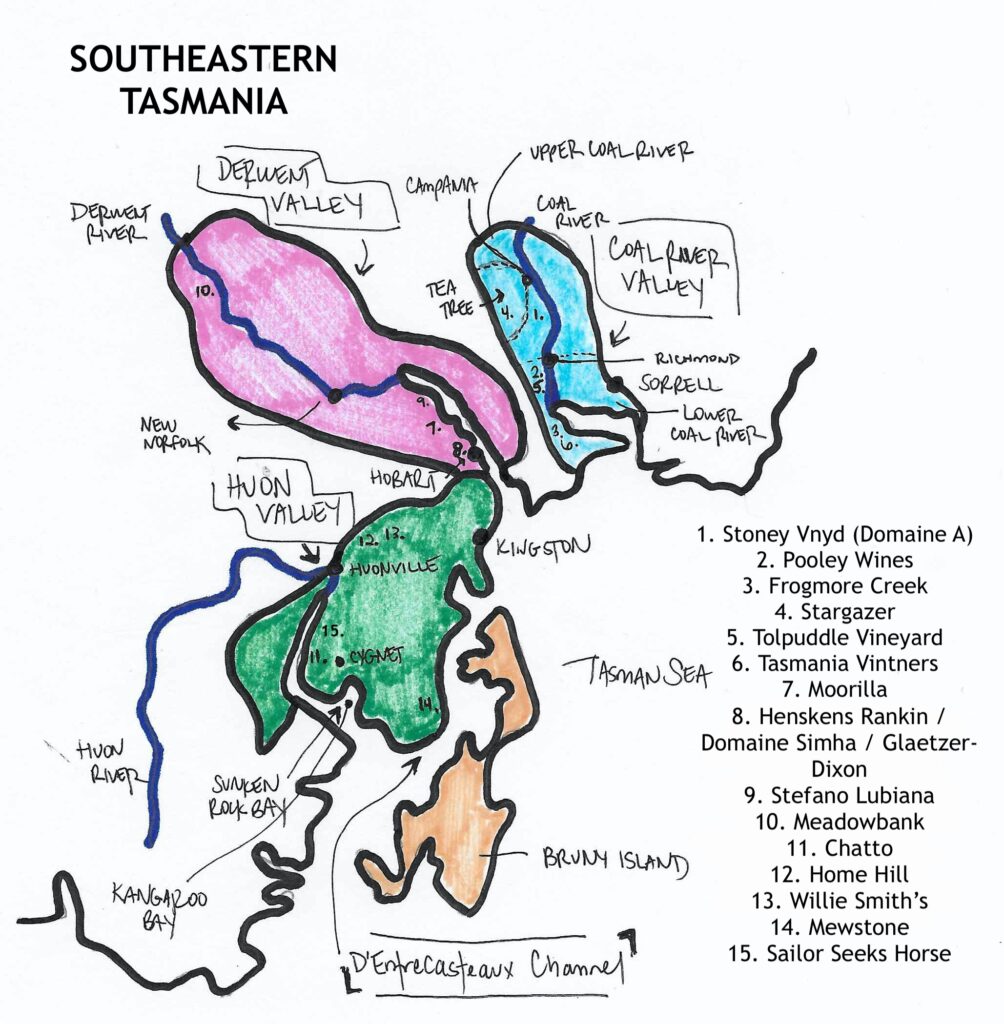

The South Eastern coastline of Tasmania is made up of a variety of rivers, lagoons, bays, small islands, estuaries and peninsulas. It is home to the Coal River Valley, Derwent River Valley, Huon River Valley, and the newer established growing area around the D’Entrecasteaux Channel. These growing areas all surround the city of Hobart with vineyards ranging from a 15-minute drive out of the city to about an hour. They are the most visited wine regions of Tasmania, and this general area supports the most diverse set of grape varieties and expressions of wine produced in the GI.

The Coal River Valley begins just a 20-minute drive to the northeast of Hobart, and extends north through the Coal River Catchment. Vineyards mainly sit to the west of the Coal River between it and the Derwent River. The valley is one of Tasmania’s driest areas with a 10-year rainfall average of just under 500ml per year, a decrease of nearly 10% from the previous 10-year average. Rainfall was somewhat evenly spread throughout the year, but in recent years it has become quite condensed, with over 20% of 2020’s expected rainfall occurring in August alone. Three areas can be carved out of the Coal River: Lower, Upper, and Tea Tree, though climactically they don’t differ greatly. Tea Tree, slightly further from the river itself, sees a touch more rainfall, and a bit more of a temperature swing, though there is only a distance of about 25k from end to end of the Coal River Valley.

The lower section of the valley is defined as being downstream from the town of Richmond toward the coast. Tolpuddle, Frogmore Creek, and Tasmania Vintners are a few of the notables here. Tasmania Vintners was formerly called Winemaking Tasmania (a custom crush facility), before it was purchased by the Fogarty Wine Group, who has brought significant land ownership and acquisition ambition to the company. Many wineries of the lower Coal River Valley boast plush cellar doors and capture a lot of wine tourism coming out of Hobart.

The Upper Coal River Valley is a touch more spread out, but is quickly becoming as dense as the lower. It was established before the lower section, with Domaine A’s Stoney Vineyard being planted in 1973, but it’s seen less consistent development. It’s only another 10k further north out of Hobart, and is a hotspot for external investment into Tasmania. Anna Pooley’s eponymous winery straddles the line between upper and lower, based right in the town of Richmond, but with much vineyard land further north in Campania. The area known as Tea Tree sits to the west with plenty of new vineyards and investment arriving. The first two vineyards in the area, Morningside and Pages Creek, were established in the 90’s, with Stargazer running a vineyard planted in 2004 along Back Tea Tree Road. Nick Glaetzer has also planted a vineyard in Tea Tree, which he expects a first harvest for in 2021.

Vineyard plantings throughout the Coal River Valley are diverse and range from red and white Bordeaux varieties planted by Domaine A (who is now owned by Moorilla) to chardonnay and pinot noir in a range of micro-climates throughout the valley. Riesling finds a home as well and is reared to produce everything from lean and mean Clare Valley-styled expressions, harmoniously dry ones that find superb balance between acid, weight and small amounts of residual sugar, and rich dessert wine.

The Derwent River Valley extends inland and east from the city of Hobart, which sits at the mouth of the river. It gets slightly more rainfall than the Coal River Valley, and varies a bit more as one travels inland from the Derwent Estuary to the Upper Derwent River. Hobart, Australia’s second driest city and home to Australia’s first commercial winery, sees about 625mm of rain annually, while the inner-most areas of the region near New Norfolk see about 530mm of rain annually. The region is renowned for a variety of agriculture, from hops to apples and apricots, potatoes, poppies and potatoes. Hobart also houses several micro-negociant or hybrid grower/negociant producers, like Henksens Rankin, Domaine Simha, and Glaetzer-Dixon, who source grapes from a variety of vineyards and make wine in the city’s suburbs. These producers are not to be discounted; they represent some of the best and most ambitious wine coming out of Tasmania.

Late winter frost is the most concerning viticultural hazard in the Derwent. The plentiful natural water sources throughout Tasmania, and in particular the southeast, make access to water for irrigation abundant. The region’s first vineyards are those of Moorilla, planted in 1958 by Claudio Alcorso and now under the ownership of MONA. In 1990, Stefano Lubiana established his first vineyard further upstream and produces a variety of biodynamic still and traditional method sparkling wines that have risen to the top of Tasmania’s output. Further upstream, high in the Derwent Valley, sits Meadowbank, a well-esteemed and critically-acclaimed vineyard that started to take form amidst a sheep farm in 1976.

The Huon Valley is yet further southwest, reaching below the 43rd parallel. The Huon River originates in the mountains to the west, meanders through Lake Pedder, then is joined by a series of other tributaries and meets the Sunken Rock Bay before emptying into the D’Entrecasteaux Channel and then the Tasman Sea. The upstream town of Huonville and the Kangaroo Bay-side town of Cygnet frame the Huon Valley. Vineyards are spread throughout the region. Some sit on the eastern bank of the river along the 15km stretch between Huonville and Cygnet. Top producers from this area include the pinot noirs of Jim Chatto’s eponymous estate and the chardonnay and pinot noir expressions from Sailor Seeks Horse. Other producers include Kate Hill and Elsewhere Vineyard.

About 20km east of the town of Cygnet, looking out onto the D’Entrecasteaux Channel and across from Bruny Island, is an unnamed peninsula. The eastern coastline of the D’Entrecasteaux Channel has often been lumped into the Huon Valley, though its producers are championing a separate identity. Mewstone is the area’s leading vintner, with a variety of expressions of pinot noir and riesling. As one would expect, there are vineyards across the channel on Bruny Island. These are just getting started, but certainly add to the novel experience of visiting the island. It’s home to some of the purist oyster beds in the world–an awesome day trip from Hobart. The Huon Valley is also home to Tasmania’s most vibrant apple orchards with numerous cideries including the historic Willie Smith’s, that’s been going strong since 1888.

As a wine region, Tasmania is unique and exciting in the world of wine. In a relatively small area, it has the ability to create interesting and delicious wines from a broad spectrum of grapes, and with fairly unrestricted access to irrigation, agriculture thrives. A fortuitous set of circumstances created a viticultural landscape that in some ways resembles the rolling grasslands of Central Victoria, and is met with the cold windy climate of Roaring 40’s. The future of Tasmanian wine is certainly bright and full of prosperity. Hopefully the First Nations of Tasmania, as well as its small farmers and winemakers, will share in what’s to come.

Tasmania's Future as Seen through the Climate Atlas

Notes and Definitions

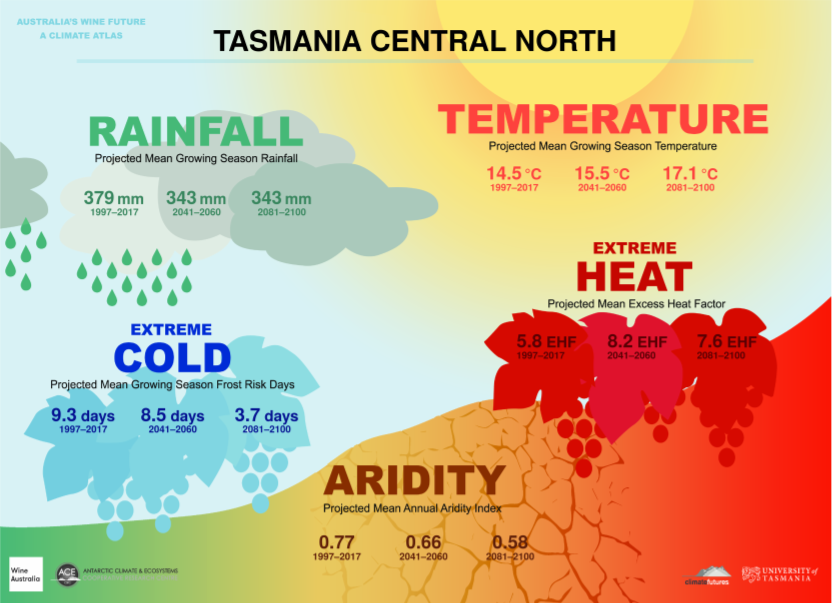

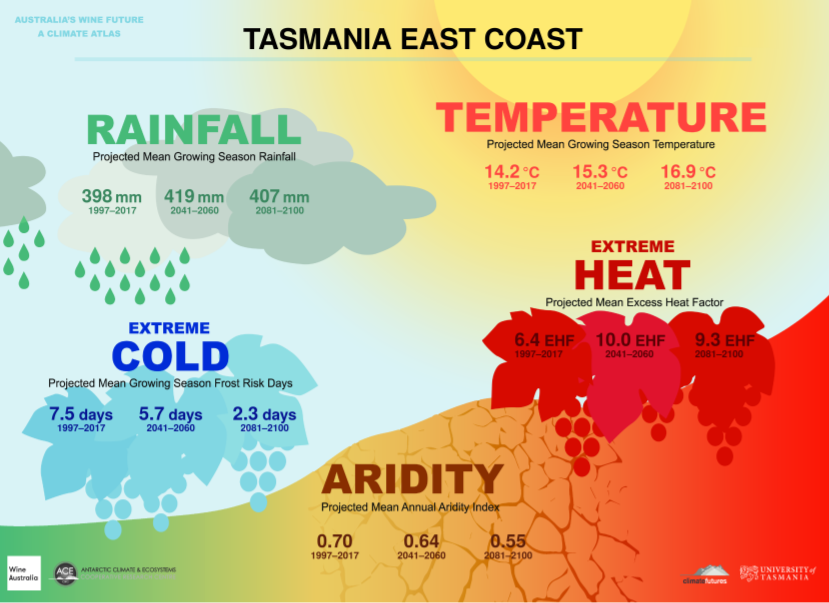

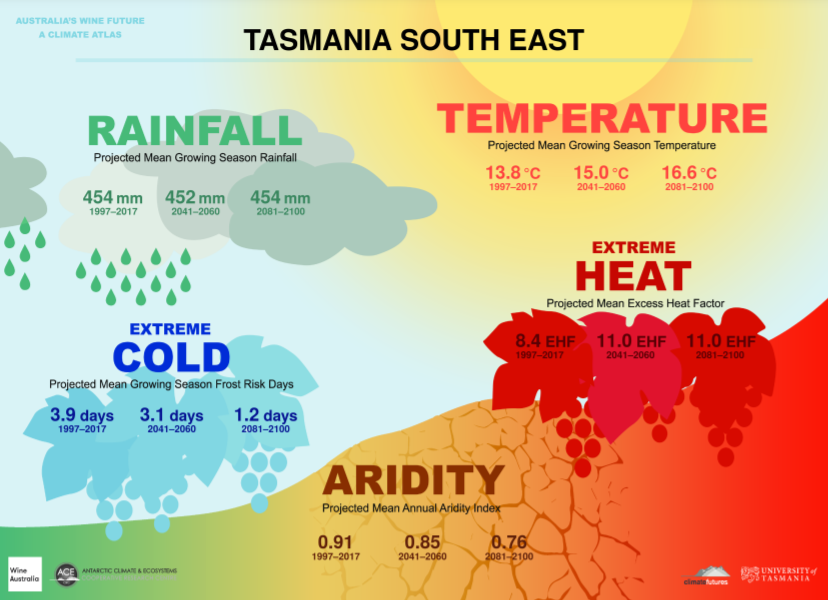

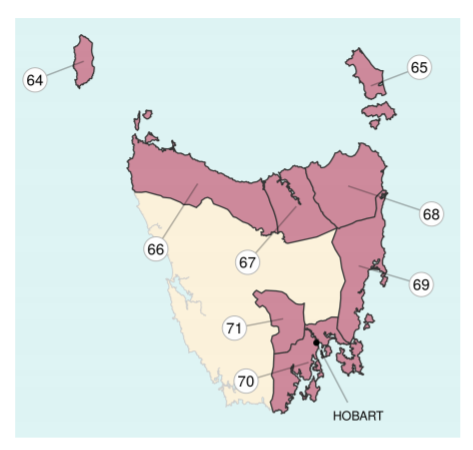

The application of the Climate Atlas to Tasmania is broken into 8 different areas. These are not registered GIs, but rather divisions that are based on marked changes in climate based on their designated area. 3 of these 8 are shown for example.

Tasmania's 8 Climate Regions

64 - King Island; 65 - Furneaux Islands; 66 - North West Coast; 67 - Central North; 68 - North East; 69 - East Coast; 70 - South East; 71 - Upper Derwent Valley

- Growing Season is defined as the 6 month period from October 1st through April 30th, and is the time frame referenced by the Rainfall, Temperature, and Extreme Cold indexes.

- The Aridity Index uses an annual picture rather than the specific growing season within the year. It indicates the availability of water by measuring the accumulation of water against the evaporation of water, and represents the difference between the two. It does not take into account soil types, shading, changes in farming practices, or vine schematics (material, planting density, irrigation), but does take into account slope, aspect, elevation, humidity, and the effects of wind patters. There are few places in the world where rainfall is expected to increase at an equal to or higher rate than the increase in the rate of evaporation, so the entirety of Australia is expected to become increasingly more arid along with most of the world’s wine regions.

- Heat analysis and projections come with a high level of confidence across the climate analysis industry. Projections are linked to emissions models, and span a variety of well understood variables.

- The Extreme Heat Factor is used to measure the effects short-term intense heat experienced during heat waves have on humans. This factor is based on the three-day time period definition of a heat wave as it relates to the preceding 30-day temperatures of a specific place. Heat waves are large scale events that do not depend on specific regional details, and therefore the data relies more on overall climate change.