Wrattonbully

Orientation

Sometimes the taxonomy of wine regions can be confusing, which is certainly the case for Wrattonbully. Located over 100 kilometers from any coastline, Wrattonbully proudly boasts its membership within the greater Limestone Coast zone of South Australia’s GI structure. And though “limestone” is clearly apt – Wrattonbully is home to limestone caverns that are a valuable window into millions of years of natural history – “coast” is actually not as incorrect as one might think: the region sits on a ridgeline that was once the southernmost coastline of the super continent that formed as Pangea began to break apart.

Wrattonbully is nearly a midpoint on the inland route between Melbourne and Adelaide: a mainly flat drive through grassy plains and rolling hills. As you head west from Melbourne, past the Grampians toward the South Australian border, you exit the western reaches of the Great Dividing Range. The dynamic topography built on granite and metamorphic soils turns into plains that were once seabeds. It’s moments like this—driving across large swaths of land that were once at the bottom of the ocean—that renders Australia so skilled at making humans feel tiny and inconsequential.

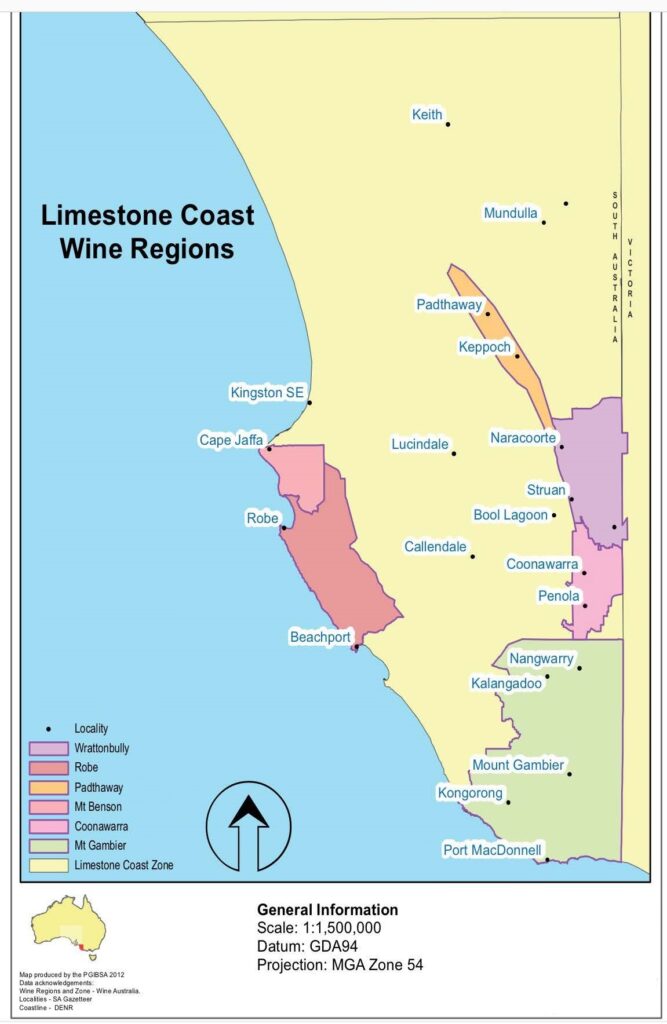

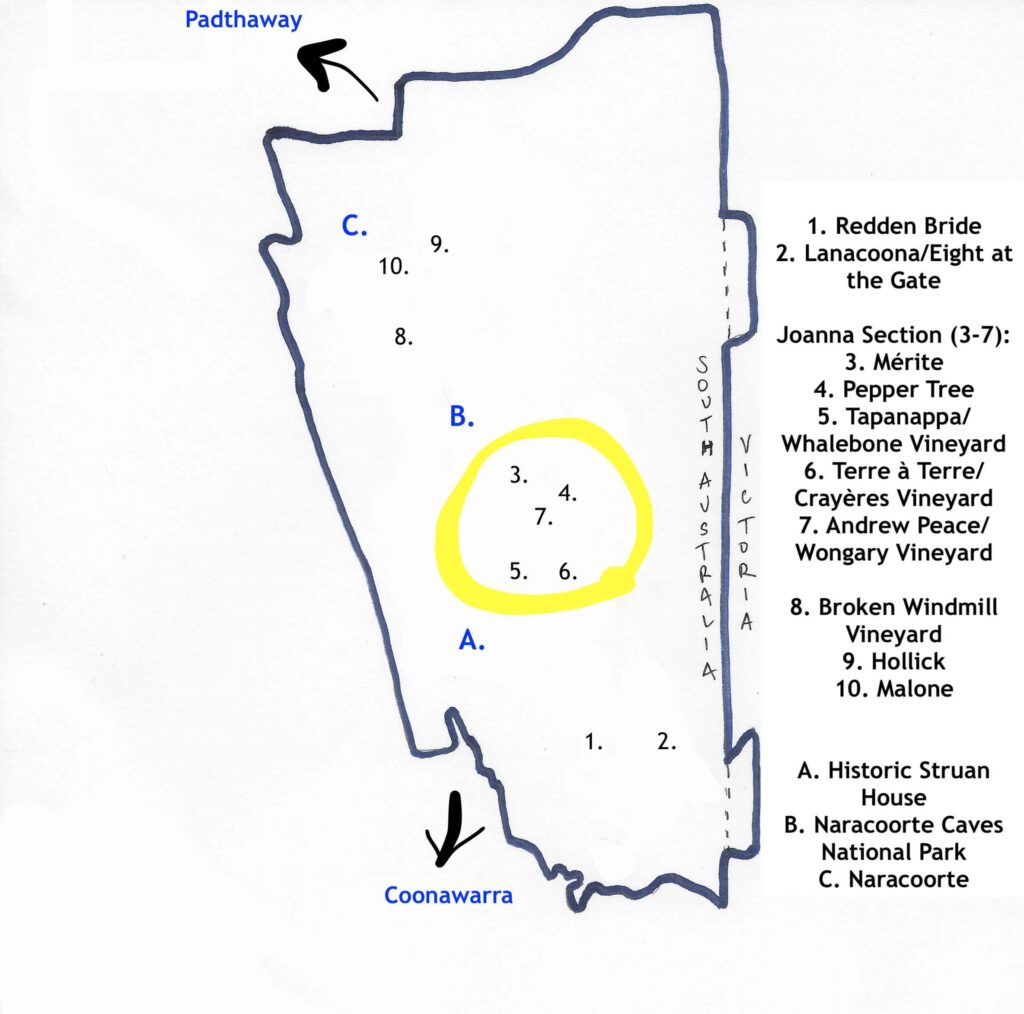

Wrattonbully crops up as a moderate elevation outpost. Its eastern border marks the border between Victoria and New South Wales. It is sandwiched between the famous Coonawarra GI to the south and productive Padthaway GI to the north. Its registration as a GI in 2005 makes it a late-comer to the game, currently working to establish its brand and identity as the premium wine region that it is.

Geological History and Climate

As the seas receded about 1 million years ago, various ridgelines and mountain ranges appeared as temporary coastlines. Prior to the waters receding, the southern coastline of the continent was drawn by the northern limit of the Otway Basin (in the modern-day Geelong GI, along the route from Melbourne to Wrattonbully). The ancient seabed soils in this area have been covered by volcanic activity (check out our Geelong guide to learn more). The Kanawinka Escarpment, more commonly known as the Naracoorte Ranges, was a checkpoint in the receding movement before the current modern-day coastline formed. It is along the Naracoorte Ranges where we find the modern-day GIs of Coonawarra and Wrattonbully.

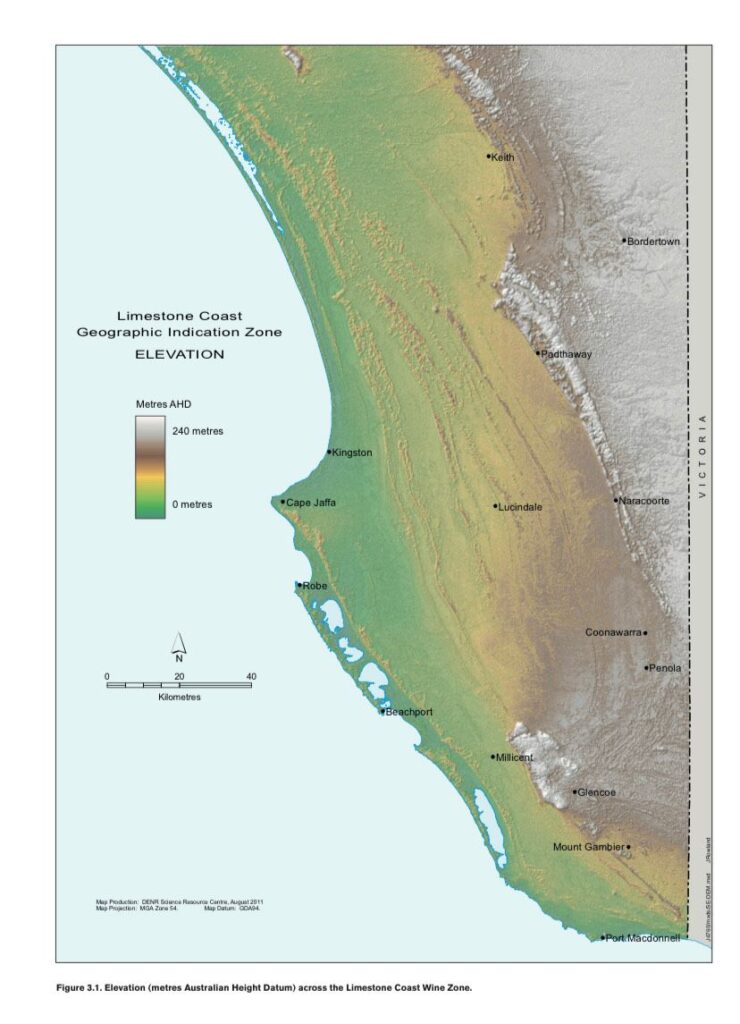

The Naracoorte Plateau (aka Kanawinka Escarpment) sits at higher elevation than much of the rest of the Limestone Coast. The areas of “Dune Limestone” identified in the soil map sit at 40 meters above sea level or less, with a water table that’s often too shallow for viticulture. At the edge of the plateau, there are peak elevations. This where Wrattonbully (at 75-150 meters above sea level) and Coonawarra (at 50-100 meters above sea level) sit.

Here, we see the soil deposits that have migrated from the Murray Basin and mixed with decomposing clay to form the famed terra rossa soils.

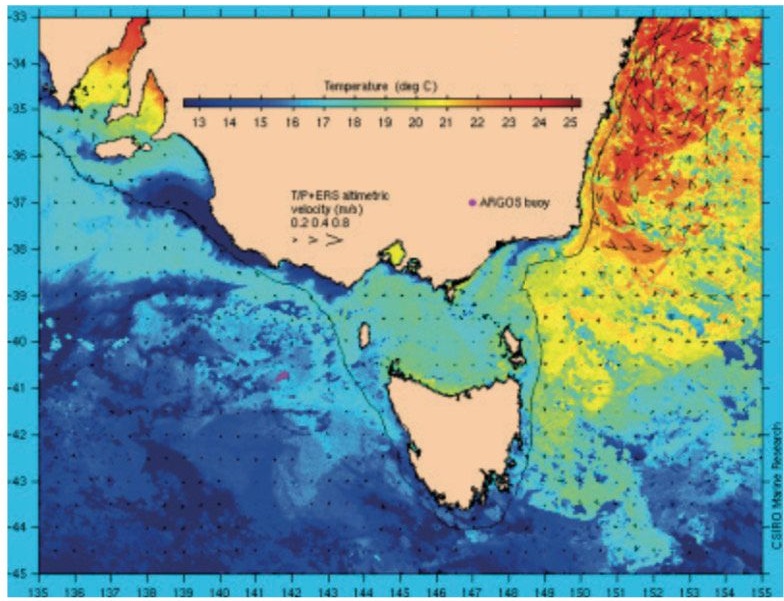

Another important influence on this region is the Bonney Upwelling. An upwelling is a natural tidal phenomenon, where very cold waters rise to the surface for a few months each year, bringing with them nutrient-rich sea life. Upwellings often equate with whale-watching seasons, as this sea life (namely phytoplankton) attracts the whales to the surface.

The Bonney Upwelling extends from Portland, a city in Victoria along the Great Ocean Road, about an hour from the South Australian border, and Robe, in the Limestone Coast zone of South Australia. The map to the right shows the huge difference in water temperature seen during this upwelling, which coincides with the start of the ripening period for grapes in the Limestone Coast, early November through early February. Cool waters during this integral grape-growing moment produce a sizable diurnal swing (difference between daytime and night-time temperatures), which contributes to high tannins and acidity in the region.

The comparison to Bordeaux is natural here, given the similar soil types (especially to the right bank of Bordeaux) and the Limestone Coast’s proclivity to grow Bordeaux grapes (cabernet sauvignon and merlot, especially). Wrattonbully’s climate is similar to that of Bordeaux in terms of heat summation. Both sit in a Region II range, fairly cool when compared to Barossa’s Region IV situation. Wrattonbully is quite a bit drier than Bordeaux, however (around 200 mm of rainfall each year, compared to the 900+ that Bordeaux sees). This allows for far less disease pressure, but the great need for irrigation. Wrattonbully also enjoys a much higher elevation than Bordeaux, the 75-150 meters mentioned above, in comparison to Bordeaux’s rather flat 18-meter altitude.

The geographic area of Wrattonbully is unique from its more famous neighbor to the south, Coonawarra, and its more productive neighbor to the north, Padthaway. Of the three that can boast terra rossa soils, Wrattonbully enjoys the highest altitude. While a nominal amount, topping out at around 150 meters above sea level, there are important benefits. The red clay soil that sits atop the ancient limestone reefs and seabeds is thinner here, and the land less fertile. This creates better drainage, less vine vigour, and a slightly more alkaline soil. Vines produce smaller berries with more concentrated flavors and, on average, slightly lower levels of pH (which results in higher acidity).

Overall, Wrattonbully offers a moderate to cool climate, dry, with elevation and the Bonney Upwelling creating a strong diurnal swing. Combined with iron-rich clay and limestone soils, an ideal climate for Bordeaux varieties emerges; but Australia cannot ignore its beloved shiraz, which along with chardonnay, round out the top grapes planted in Wrattonbully.

History of People

The greater area of the south-eastern portion of South Australia—from the Lower Murray River watershed, to the coastline from Lake Alexandria south to Cape Jaffa—is the traditional land of the Ngarrindjeri Nation. The inland reaches of this First Nation are defined by and include stark rises in the topography. The calcareous dunes noted in the above graphic are stable and covered with vegetation, in this case scrub gum and grass lands. The stretch of the Kanawinka Fault line that runs from just north of Naracoorte, south to Penola, draws the interior reaches of the Meintangk language group, one of the 18 language groups that make up the Ngarrindjeri nation. The boundaries of the Meintangk land run from the interior hills to Cape Jaffa on the coast, and is met by the Bungandidj nation to the south and the Jardwadjali nation to the east.

The lakes and waterways of the Lower Murray River – well north of Wrattonbully – were the most densely populated areas of the Ngarrindjeri nation, one of the most populated First Nations of all of Australia. The natural environment provided for a diverse and healthy diet, yielding the Ngarrindjeri as one of the stronger nations, both physically and through trade, with surrounding inland nations. Many of these nations lived and thrived along the Murray River all the way to its origin: a system of freshwater lakes in the Snowy Mountains of New South Wales. Archaeological studies show that the traditional lands of the Ngarrindjeri nation had been inhabited by humans for at least 8,000 years.

By 1790, sealers and whalers had set up a camp on Kangaroo Island, part of the Kaurna Nation, as well as on the entire eastern coast of the Gulf of Saint Vincent, where Adelaide is centered today. These men were commonly fugitives of the European jail colony setup in Tasmania. They would bring enslaved Tasmanian Aboriginal women with them, attack and capture Kaurna women that resided on Kangaroo Island, and by 1806 were raiding the mainland for more. They often targeted the Ramindjeri language group, whose settlement was located at Raukkan along the shores of Lake Alexandria. At the time, this was the most densely populated place in all of Australia.

In 1828, European colonizers in Sydney began to explore the rivers of western New South Wales. Some explorers were convinced that there was an inland sea that the rivers led to, and in 1830 a British captain named Charles Sturt sailed a whaling boat downstream along the Murrumbidgee River to the confluence of the Darling. He continued to the Lower Murray River until finally reaching Lake Alexandria and the Southern Ocean. This was the first known time that European Colonizers stepped onto Ngarrindjeri country. Sturt recorded that the Ngarrindjeri people were already familiar with firearms, likely from either trading with the Kaurna nation or dealing with whalers attempting to raid their lands.

The United Kingdom passed the South Australia Act in 1834 to empower the settlement of South Australia as a British province. As new settlements along the Lower Murray River and its watershed drew irrigation out of the river systems, the flow to the mouth of the Murray decreased substantially. Estuaries lost their freshwater inputs resulting in seawater creeping upstream, drastically changing ecosystems and causing staples of fish and other wildlife to disappear.

In 1835, the South Australia Company formed to start selling “wild land” to settlers planning to sail there. Note, that just five years prior, not a single European had touched the lands of South Australia with the aim of staying there. Four ships carrying a total of 117 passengers set sail for South Australia from Sydney in 1836. All landed on Kangaroo Island briefly before the mainland, landing at today’s Glenelg Beach in Adelaide. By this time, the Kaurna population had declined to about 700 people, and the Ngarrindjeri Nation to about 6000. Much of this population decline was a result of a smallpox epidemic that was brought from those travelling down the Murray River from the east, infecting First Nations along the way.

In the early 1840s, a “Protector of Aboriginals” post was created by the British to foster peaceful relationships between colonists and the Kaurna and Ngarrindjeri Nations. This included efforts to “educate” the Ngarrindjeri and Kauran people on religion, language, modern farming, and trade. They were employed to process whale oil, and would be paid in alcohol, tobacco and meat. A proclamation was made to the European colonizers that preserved the rights of “native inhabitants”. There was a clear effort to peacefully co-exist from the British government, but this was deeply seeded with assimilationist ideals, not ones of equality.

At Raukkan, a large settlement of the Ramindjeri language group on the banks of Lake Alexandria in the Ngarrindjeri nation, a missionary was established in 1859 that included a school, a church, and a trading post. Parts of the Bible and schoolbooks were translated into Ramindjeri language, and a western-style farm was built where Ramindjeri people learned to farm like the Europeans. This nearly 300-hectare farm was not considered “owned” by the Ramindjeri, though it was built on their traditional lands. The Ngarrindjeri nation was becoming “de-tribalized”, and there were mixed sentiments from European colonists about whether the dwindling size of this population was a positive or negative.

Raukkan has been an Aboriginal reserve since 1916, and the settlement has remained a part of the Ngarrindjeri Nation. It is the only Aboriginal Australian community within 100k of a current Australian capital city (Adelaide) that has been a constant traditional land of a First Nation. This is a result of both the sheer size the Ngarrindjeri Nation, and the interest of both British and local governments to co-exist with, rather than displace or kill, these First Nations.

In the years that followed, the Ngarrindjeri nation, like many First Nations of Australia, suffered incidents of violence and tragedy, legislation that resulted in loss of traditional lands, and economic hardships. There has been some progress made to right some of these wrongs, and to further acknowledge the traditional custodians of the land. The Ngarrindjeri nation in particular has been one of the more successful First Nations in working towards a fair and equitable co-existence, as well as garnering the acknowledgement they deserve as the first people of the land. But even they have suffered greatly at the hands of the colonizers.

The British Colony of South Australia was established as a free, non-convict colony, which attracted many farmers, businessmen, and artisans looking to prosper in an unsettled land. Victoria’s gold rush opened up Robe as a port: this modern-day Limestone Coast town allowed settlers to avoid Victoria’s tax for new arrivals. As they made their way across to Victoria, working and living in tent cities, they ended up building many of the stone woolsheds and limestone outposts that still speckle the landscape.

The majority of colonists came from England, Wales, and Scotland, as well as some German emigrants fleeing religious persecution. The first vineyard of South Australia was planted in 1836 within the modern-day city limits of Adelaide – the same year the colony was formally established. The 1840s brought a surge of travel north to the Barossa, and many of the household wineries we know today established their first vineyards through the 1840s and 1850s.

The wine regions of Wrattonbully and Coonawarra have a similar origin story. Farmland was established as the South Australian colony expanded, and small attempts at viticulture were initiated. The Barossa was well established, however, by the time these experiments started in Wrattonbully and Coonawarra in the 1880s.

Modern Viticulture

Despite early attempts at planting, the modern story of wine for these regions began in the 1950s and 1960s, when grapes were planted for the production of “table wines” rather than the fortified wines made in the 19th century. The town of Wrattonbully was established shortly after WWII as a soldier settlement where farmland was allocated to returning soldiers. Sandwiched between Naracoorte and Joanna, and with a population of fewer than 700 people, Wrattonbully was established as its own municipality decades later.

These returning soldiers were the ones who cleared the land for western farming practices and started the local sheep and cattle businesses that thrive to this day. Knocking down trees was a difficult proposition: as the local eucalyptus trees are red gum (one of the hardest types of eucalyptus), many of the largest trees – much to the relief of the modern-day preservationists – were unable to be cut down, and still remain amongst the vineyards. The choice of felling method for those large trees was ringbark: stripping the bark all around the tree as a way to cut off nutrients passed through the phloem (the layers directly beneath the bark). For large trees with good underground water supply, this proved to not be enough. Many of these trees remain to this day, still with signs of their ringbark. They act as land-markers for the best underground water sites, provide frost protection for grapes, and host kookaburras, yellow-tailed black cockatoos, beehives, owls, and local fungi.

The first plantings in Wrattonbully date back to 1969, when 11 hectares of shiraz, cabernet sauvignon, and chardonnay were planted by the Pender family (a vineyard which would come an important site for Petaluma). These plantings were followed by John Greenshields’ Koppamurra Vineyard in 1974, planted to four hectares of cabernet sauvignon. This site was later purchased by Tapanappa and renamed the Whalebone Vineyard. “Koppamurra” was on the table when naming the GI in the early 2000s, but ultimately Wrattonbully won out. Some locals still casually call the region Koppamurra.

Plantings in Wrattonbully topped out at about 20 hectares in the 1970s and 1980s, until larger, multi-regional producers scouted land in the 1990s, establishing over 1800 hectares of vineyards. Today, 85% of Wrattonbully’s 2600 ha of vineyards are devoted to cabernet sauvignon, shiraz, and merlot. Chardonnay, pinot grigio, malbec, sauvignon blanc, and pinot noir make up the majority of the remaining plantings, with some others peppered in at smaller amounts. Sweet wine actually sees a bit of airtime too, with some “stickies” made from viognier and pinot gris on the market.

The GI of Wrattonbully wasn’t codified until 2005, and came about as a result of Coonawarra seeking to redefine and tighten its boundaries. Most grapes – historically and to this day – are used in multi-regional blends or as a minority component in a Coonawarra-labelled wine. The branding of Wrattonbully – on wine lists, on bottle labels, or in wine guides – has been severely lacking.

There are only 20 different growers in the region, with about 50 different producers working with fruit from Wrattonbully. Producers vary greatly, but very few are growers that are actually making their own wine—most grapes are sold, due to strong demand, to wineries outside of the region. Treasury Wines Estates, Accolade, Pernod Ricard, Casella Family Brands, and Taylor’s/Wakefield (large multi-brand wine companies) and (formerly)Chinese negociants account for a majority amount of purchased Wrattonbully fruit. The GI is also an important source for top wines produced by Penfolds – its attention climbed the ladder when grapes from a vineyard in the Joanna section of Wrattonbully was selected to be in the 2014 Penfolds Grange. Today, Wrattonbully grows the backbone of Penfold’s 389, 707, and Grange.

These wineries can clearly see what Wrattonbully has to offer—a higher elevation version of Coonawarra, with a greater concentration of limestone in the soils, and better access to high-quality natural aquifers underground (which provide a huge benefit for frost protection). Wrattonbully has also historically offered a better value than Coonawarra, though well-deserved premium price-tags are beginning to be commanded.

Pepper Tree, a producer based in New South Wales’ Hunter Valley, purchased a 100-hectare vineyard in Wrattonbully, and produces an entire line of wines from this vineyard. Hunter Valley’s Brokenwood also uses Wrattonbully fruit for their multi-regional shiraz blend. Langhorne Creek’s Bleasdale owns a vineyard in Wrattonbully called Faraway that also contributes to their multi-regional blends. Cape Jaffa in Robe makes a high-end shiraz from Wrattonbully. Coonawarra’s Hollick maintains a vineyard in northern Wrattonbully. Yalumba and the Hill-Smith family have added Wrattonbully to their stable as well, even establishing a label dedicated to Wrattonbully called Smith & Hooper.

Terre à Terre and Tapanappa deserve much credit for putting Wrattonbully on the map. Tapanappa was founded as a collaboration between famed-viticulturist Brian Croser, Christian Bizot from Champagne’s Bollinger, and Jean-Michel Cazes from Château Lynch-Bages. They founded the estate with the purchase of the Koppamurra vineyard in 2002 (before the Wrattonbully GI had even been codified) and renamed it the Whalebone Vineyard. Christian’s son Xavier married Brian’s daughter Lucy, and the two formed Terre à Terre. They purchased the Crayères vineyard in 2004, a prime site next door to the Whalebone Vineyard in the Joanna section of Wrattonbully. Both estates vinify in Piccadilly Valley, Adelaide Hills.

Another single vineyard site that merits mention is Broken Windmill, which was planted by Peter Bissell and Louise Dickens in 1999. Until recently, Peter was the long-time head winemaker at Balnaves of Coonawarra and Louise a viticulture expert specializing in entomology and plant pathology. They are a team on this vineyard project, though they have yet to venture into making their own wine.

Similarly Mérite, based in the Joanna section of Wrattonbully, had previously sold most of their grapes for high-end multi-regional blends, but from the 2015 vintage have begun estate bottling. They craft age-worthy wines from merlot, cabernet sauvignon, malbec, and shiraz, and are beginning to see national and international attention.

There are a handful of other small vineyards making Wrattonbully-labeled wine – Malone, Redden Bridge, Eight at the Gate, Andrew Peace, Pavy – but few are known outside the region.

All of these producers vinify outside of Wrattonbully, though. The astonishing truth of Wrattonbully is that there is only one winery facility within the GI—and it is closed and up for sale! Wrattonbully is a region of vineyards. The people who are making the big difference in the future of Wrattonbully are the skilled growers producing quality grapes, and the producers – like Mérite, Terre á Terre, Tapanappa, Yalumba, Pepper Tree, and Smith & Hooper – who proudly announce Wrattonbully on their labels.

Wrattonbully is truly one of the best kept secrets in the wine world. Producers from near and far know the quality and value found in the GI. And those with a vested interest in keeping it at that value – producers bottling Wrattonbully fruit as part of their Coonawarra range or in a multi-regional blend – have no interest in seeing brand Wrattonbully appreciate.

But appreciate it should. There seems to be a global renaissance afoot that is recognizing great expressions of Bordeaux varieties again. Wines with chiselled and articulate tannins that fold into ripe and balanced fruit are increasingly sought after, and Wrattonbully is perhaps the top of class for that quality in South Australia. There is much for sommeliers, retailers, and consumers to discover and re-discover in this region. Wrattonbully’s future surely seems like a bright one.

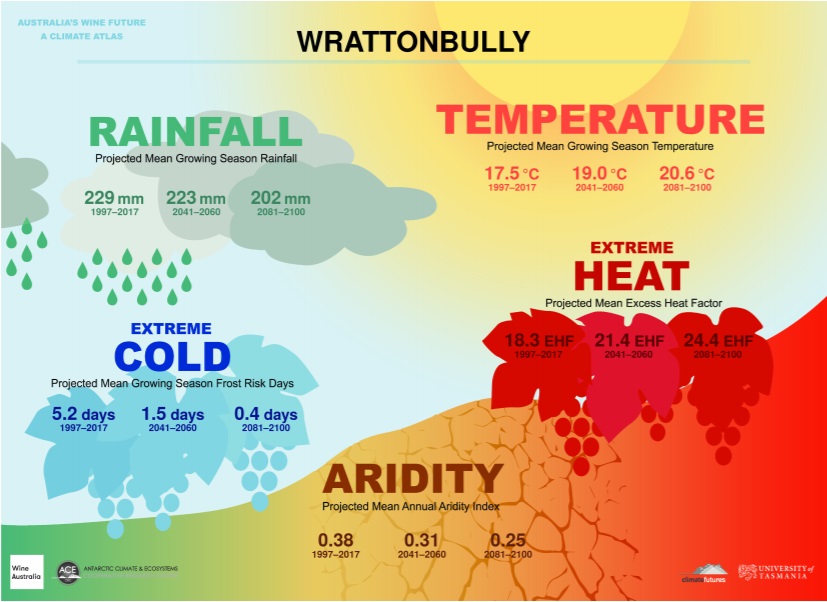

Wrattonbully's Future as Seen Through the Climate Atlas

The Climate Atlas is the culmination of a three-year study lead by the University of Tasmania, and analyzed 70 years of historical data across every Australian GI. Their predictions are based on this history, and present crucial metrics to understand what the next 80 years of climate change will bring to Australian viticulture and greater human life.

Notes and Definitions

- Growing Season is defined as the 6 month period from October 1st through April 30th, and is the time frame referenced by the Rainfall, Temperature, and Extreme Cold indexes.

- The Aridity Index uses an annual picture rather than the specific growing season within the year. It indicates the availability of water by measuring the accumulation of water against the evaporation of water, and represents the difference between the two. It does not take into account soil types, shading, changes in farming practices, or vine schematics (material, planting density, irrigation), but does take into account slope, aspect, elevation, humidity, and the effects of wind patters. There are few places in the world where rainfall is expected to increase at an equal to or higher rate than the increase in the rate of evaporation, so the entirety of Australia is expected to become increasingly more arid along with most of the world’s wine regions.

- Heat analysis and projections come with a high level of confidence across the climate analysis industry. Projections are linked to emissions models, and span a variety of well understood variables.

- The Extreme Heat Factor is used to measure the effects short-term intense heat experienced during heat waves have on humans. This factor is based on the three-day time period definition of a heat wave as it relates to the preceding 30-day temperatures of a specific place. Heat waves are large scale events that do not depend on specific regional details, and therefore the data relies more on overall climate change.