Ranging From Serious to Seriously Fun

This post is part of an ongoing Q & A series with our growers and winemakers. The idea is for you to get to know them a bit better, as well as the country of Australia and its wine.

If you were to have a career besides being a winemaker, what would it be?

“I’d like to be a talk-show host & talk & listen to fascinating people from all walks of life.”– Glen Robert, La Petite Mort (Granite Belt, Queensland)

“Tennis Pro.”– Leighton Joy, Pyren Vineyard (Pyrenees, Victoria)

“I am lucky enough to do my favorite job other than being a winemaker. I make documentary films about art and artists. I am currently producing a new short film by a young filmmaker based in Yirrkala. Her name is Siena Stubbs and she is the youngest winner of the Telstra Multi Media prize, the most important prize in Aboriginal Art. She is 18 years old!!”– Dennis Scholl, Mother Tongue (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

“Already had one of those, I was a research scientist (agriculture/plant physiology), now I’d say writer but I’m too lazy (not to mention untalented).”– Frieda Henskens, Henskens Rankin (Hobart, Tasmania)

“Book shop owner or librarian.”– Samantha Connew, Stargazer (Coal River Valley, Tasmania)

“A psychologist.”– Sierra Reed, Reed Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“Reality: restauranteur. Fantasy: astronaut.”– Jonathan Ross, Micro Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“Stumped. This is it.”– Niki Nikolovski and Tim Byrne, Babche (Geelong, Victoria)

“A nurseryman or a carpenter. I love growing plants and making things from timber.”– Mark Walpole, Fighting Gully Road (Beechworth, Victoria)

“Farmer.”– Michael Downer, Murdoch Hill (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Composer.”– Kim Chalmers, Chalmers (Heathcote, Victoria)

“Landscaper.” – Bart van Olphen, Chalmers (Heathcote, Victoria)

“Truck driver.”– William Downie (Gippsland, Victoria)

“Working in BioTech.”– Patrick Sullivan (Gippsland, Victoria)

“A luthier.” – Matt Harrop, Silent Way (Macedon Ranges, Victoria)

“I was previously a horticulturist, which was fun, but I didn’t enjoy it as much as I enjoy making wine. I’d happily travel, look at art and listen to music for a living…is that a career? Or playing Rugby for Australia.”– Andy Cummins, Rasa (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

“I’m working on writing a book of our experience of leaving the US to buy a farm and building a vineyard.”– Collen Miller, Mérite (Wrattonbully, South Australia)

“Teaching children to read – literacy is critical for the best start in life.”– Fiona Donald, Seppeltsfield (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

This post is part of an ongoing Q & A series with our growers and winemakers. The idea is for you to get to know them a bit better, as well as the country of Australia and its wine.

What is your favorite part about your job?

“Walking the vine rows.”– Colleen Miller, Mérite (Wrattonbully, South Australia)

“Seeing people enjoying the wines I’ve made.”– Michael Downer, Murdoch Hill (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Being outside on the farm.”– Erinn Klein, Ngeringa (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Vineyard assessment, tasting and blending.”– Fiona Donald, Seppeltsfield (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

“There aren’t many jobs in the world where you can enjoy socially what you do professionally. Winemaking is that for me. I get just as excited making my own wine as I do thinking about and drinking other people’s wines.”– Andy Cummins, Rasa (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

“Most of it. It’s a very creative pursuit. And so connected to nature, the seasons, reality. Keeps me very grounded. And bottling. A very reflective time putting wine into bottle. A couple of years work in every bottle.”– Matt Harrop, Silent Way (Macedon Ranges, Victoria)

“When I get an e-mail from one of my lovely customers telling me how much they enjoyed one of my wines, particular if it’s at a family occasion or celebration.”– Samantha Connew, Stargazer (Coal River Valley, Tasmania)

“Everything except the books; particularly I like the people-centric bits.”– Frieda Henskens, Henskens Rankin (Tasmania)

“Nature dictates what we do, she’s the bottom line.”– Niki Nikolovski & Tim Byrne, Babche (Geelong, Victoria)

“My favorite part about my job is I get to live my passion and then share it with others.”– Sierra Reed, Reed Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“Working with good people.”– Patrick Sullivan (Gippsland, Victoria)

“Lunch.”– William Downie (Gippsland, Victoria)

“Being outdoors working with plants.”– Mark Walpole, Fighting Gully Road (Beechworth, Victoria)

“Witnessing the impacts of decisions, experiments, and effort. And the energy of harvest!”– Jonathan Ross, Micro Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“Dreaming up new projects.” – Kim Chalmers, Chalmers (Heathcote, Victoria)

One of our fundamental approaches to communicating about Australian wine is to refrain from generalizing its 65 different wine regions into one innocuous category. Although in some cases, like the overall quality of a growing season, it’s somewhat hard to avoid.

There is a set of major determining factors throughout the growing season that contribute to the success of a vintage. It all starts with the previous year, and the stress, or lack thereof, the vine experienced. For some regions, vines are coming out of smoke taint, drought, heat stress, and a variety of other factors.

2020 was Australia’s worst bushfire season to date (46 million acres burned). While that was largely felt by a specific set of regions – the Hunter Valley, those in the foothills of the Australian Alps, East Gippsland, and Adelaide Hills – many regions experienced higher max temps and lower annual rainfall than their rolling averages. A drought vintage for many regions, and the 4th in a row for some. All in all, lots of stress.

The 2020 harvest was also kicking off as COVID was taking hold of the world. By mid-March, backpackers in their 20s on working holiday visas and short-term agricultural visa workers had vanished. Wineries were locking down, restricting those who were allowed onto their vineyards and in their cellars. And the usual hospitality and casual work-force movement from cities to the vineyard for harvest never happened. The extremely low-yielding vintage was perhaps the most challenging to harvest.

2021 starts with a bit of a balancing boon. Many regions experienced above average rainfall – seeing catchment dams and reservoirs at their fullest, rivers flowing strong and lakes freshly filled. Ground water and moisture levels were high, supporting a healthy budburst and initial spring push for many regions. In general spring was a milder one across the county, with a slower start to the vintage shortening the threat of frost for the cooler regions prone to it.

Outliers

- Southern Tasmania – The Coal River, Derwent, and Huon River Valleys sit in a stark rain shadow. While there is no shortage of sun in these chilly vineyards (same degree days as Champagne), the dry climate prevails.

- Western Australia – The Swan Valley had a warmer than average spring, and an earlier start. Margaret River was recovering from a hail-laden 2020 rather than one full of fire.

Further Outliers

- Tasmania received above average rainfall in 2020, though the south was recovering from the previous vintage’s bush fires.

- Similarly, the most coastal regions in Victoria received above average rainfall in 2020: Yarra Valley, Macedon Ranges, Sunbury, Mornington Peninsula.

South Australia

Accounting for over 50% Australia’s harvest, SA saw an overall top-notch vintage, though a few pockets were left behind.

The McLaren Vale, like the rest of the state, enjoyed above average rainfall through the winter. Spring warmed up quickly, and budburst was a bit earlier than average for the Vale. The mild summer, however, allowed for good hangtime, low disease pressure, and pristine fruit. La Niña vintages often bring increased cool breezes down through the eastern foothills, keeping vineyards cool and well ventilated. Harvest was spaced out, letting producers work with pristine fruit in ideal conditions. To quote one of the region’s oldest and most important producers, Coriole, winemaker proprietor Duncan Lloyd feels that “2021 will be sure to be remembered as one of the greatest Shiraz vintages in the McLaren Vale.”

Just to the north, and over the Lofty Ranges, the Adelaide Hills enjoyed a 2021 that was in stark contrast to 2020. Yields were terribly low, and bushfires tainted many peoples’ harvests. September rains were plentiful, providing food energy for budburst. November weather was perfectly mild, resulting in picture perfect flowering across the region. December usually brings a lot of heat, but not in 2021, and a mild January with sparse rain brought a gentle dry autumn harvest. Yields in the Hills are plentiful, and quality is absolutely superb. After a tough run, the Adelaide Hills has a cracking vintage on its hands!

The story of 2021 in the Barossa is best told by Louisa Rose, chief winemaker at Yalumba and Pewsey Vale: “There are no excuses for not making a great wine this year”.

Yields across the zone in both the Eden and Barossa Valleys were up. It started with plentiful winter and spring rains, some delayed budburst and flowering pushing harvest out a touch. This gave way to a mild summer and harvest with wonderful flowering phases. The only issue was some hail in isolated pockets throughout the Barossa Valley, namely in the areas tucked against the Barossa Ranges in the eastern parts of the valley near the towns of Tanunda and Vine Vale. Be on the look out for some 100 pointers from 2021!

In the Clare Valley, as well as the Limestone Coast’s Coonawarra and Wrattonbully, the story of 2021’s yield and quality boom rings true. Large harvests of ripe, balanced, articulate fruit are all anyone can talk about.

Tasmania

The island state experienced the growth in harvest yield from 2020 that the rest of the nation saw, though not quite as big a rebound as most. La Niña was in full effect here with the northern subs of Pipers River and Tamar Valley experiencing the wettest summer in 20 years. Though that only amounts to 280mm in rainfall for the growing season – about 40% up on the average. It was here where the 18% yield increase from 2020 was felt the most.

The Tamar Valley accounts for just over 1/3 of the state’s production; it saw the greatest increase, while the regions across southern Tasmania experience a more stark rain shadow, and less of the yield boom. The more marginal growing areas like the Huon (Australia’s coldest growing are) certainly saw yield increases, but remains the country’s lowest yielding area in terms of tons/ha.

2021 did, however, bring considerable growth for Tasmania. Quality is absolutely top notch, and the producers we’ve spoken too are buzzing with anticipation. It’s not limited to pinot noir and chardonnay either (both of which saw the signature Tassie millerandage). Riesling and pinot gris are looking pretty flash too. The average per ton price for fruit rose to $3,146 per, over four times the national average of $701/ton! 54% of the state’s vineyards are now managed under the Wine Tasmania’s Vin0 program, representing continued growth, as compared to just 40% in 2018. And, with new vineyards going in along with the expansion of existing ones, the future of Tasmanian wine is only getting bigger.

Western Australia

The growing regions here, especially the Margaret River, are extremely Mediterranean. They have predictable, mild climates that invite such outsider jests like ‘does Margs even have vintages?’.

However, the La Niña weather pattern has a different effect on WA than in the east. With it comes a heavy cyclone season for the tropical northern west coast, and results in extreme weather in the south.

Margaret River experienced an average winter and early spring resulted in highly favorable budburst conditions. However, November was wet, with 14 days of straight rain. December and January were dry and warm with nearly no rain at all, allowing for vineyards to rebound. In February, rains increased, and while that was a positive for the later ripening cabernet sauvignon, it increased disease pressures considerably. Some soils became waterlogged in lower quality vineyard areas further inland and to the south.

Rain events continued after whites had gone through verasion, creating a need to let them hang a bit. However, the warm and humid season increased the presence of botrytis and put further strain on the manual labor in the vineyards among wet and windy conditions. Given the lack of labor due to COVID, it was a hard run-up to harvest with few hands.

2021 produced some wonderful fruit, but it’s the best farmers and vineyard managers working the best patches of land that will come out on top, as usual. However, it’s likely a vintage that will buttress the argument to single out some of the top performing subregions, officially.

Further north in the Swan Valley, the country’s warmest GI, the vintage was even warmer than average. This might be the only GI in Australia with this commentary. All stops along the growing cycle were a touch early, including the start of harvest. Yields were a little light given the warmth of the year, which resulted in tiny bunches and concentrated flavors. Early harvests due to heat are not new to this region, so overall quality will be outstanding. Older vineyards planted to chenin blanc and grenache are particularly exciting.

Victoria

The effect of the El Niño and La Niña weather patterns are strongly felt along Australia’s east coast. With 2021 being a year of La Niña, the increased rainfall and cooler winter temperatures rang true. The amount of Rainfall rises as ocean surface temps rise, so with the climate warming some regions like the Yarra Valley experienced rainfall levels 25% higher than the 60-year average.

La Niña’s effects are longer lasting than El Niño, with the mild temps and increased rainfall lasting longer into the warmer months. A cool wet spring would bring on the expected disease pressures of downy and powdery mildew, though the absence of heat spikes kept humidity at manageable levels. Spray programs – be it biodynamic, organic, or conventional – needed to be focused, right on time and plentiful. It’s all hands-on deck vintages like these that really drive the cost of farming up, so it’s paramount to prevent the loss of fruit.

As vintage ticked on, it moved through the peak of summer without many regions toping 40 degrees save for those inland along the Murray like Rutherglen and Murray Darling. Regularly, that bountiful Australian sunshine was behind a blanket of clouds. A late drawn-out harvest for Victoria was eminent, but also welcomed after the condensed harvests of recent.

Though not an easy one, 2021 in Victoria is being called a fantastic vintage. Mild temps with rain at mainly the most desired times, with few issues of too much rain at the wrong times, has resulted in bright, focused wines with considerable power and elegance. A key indicator of quality, bunch sizes in general were quite small. Another nod to quality, color in red grapes is highly concentrated as a result of extended hangtimes achieved from the mild summer.

Some specific grapes had less fortunate outcomes: sangiovese received early autumn rain at the wrong time in Northern Victoria; Bordeaux varieties like cabernet sauvignon and semillon had difficulty ripening in the cooler coastal regions; and we’ll soon see if nebbiolo in the Yarra or grenache in Geelong was able to achieve the ripeness the grapes deserve.

New South Wales

The country’s second most productive state, responsible for just over ¼ of the annual harvest, churned out an exciting year. NSW was hit hardest by the bushfires of 2020, with the state’s most notable regions like the Hunter, Canberra, along with most of the regions among the Alps, having little if any viable fruit.

The Hunter had above average winter rainfall, but a slightly warmer winter leading to a slightly earlier bud break. Unlike a lot of Australia, the Hunter stays green through the summer, especially in more mild vintages. Harvest was a sustained, mild, and dry season that was a bit less rushed than in recent years. This afforded longer hangtimes and achieved heightened flavor ripeness at lower-than-normal pH levels. As usual, harvest was wrapped up in February, but with an excitement that the region has not felt for a few years.

Another outlier for the 2021 yield boom was Orange in the Central Ranges. This high-altitude region with a GI boundary defined by elevation had the wet chill of winter extend through October (akin to April up north), which resulted in damaged buds and poor fruitfulness of what made it through. The season in general was wet and cool, and caused for a punctuated early-ish harvest with high acid whites. Harvest rains interrupted pinot noir harvests, which caused for longer hang times, resulting in good color and flavor concentration with retained acids. The region has become well known for sparkling wine in addition to its delicate examples of still pinot noir and chardonnay. This will be an interesting vintage to see materialize, with likely some of the more varied outcomes across any single GI for 2021.

In 2020, Canberra and its neighbor Hilltops barely had a harvest. After having gone through drought, hail, and fires what was left ended up being distilled. 2021 has been, as the rest, a mild, moderate vintage with long hang times and layers of flavor developed. Canberra’s signature savory expression of shiraz and bright Riesling bottlings are being met with lots of anticipation. The region has evolved to include a number of experimental grapes that do well in warmer climates. We’ll see how the Rhône white and Italian red varieties shake out, but the mild, dry autumn should bring high quality across the entire set.

Neighboring Gundagai saw exceptional yields and a mild summer when at times it can get a bit hot. To its south, and up in the Alpine foothills, Tumbarumba took a while to emerge from the cold winter. Sitting on the western side of the Snowies, it was shielded from some of the easterly rainfall that could have waterlogged the summer. We should expect sparkling wines of power and finesse from the 2021 vintage.

Queensland

The Granite Belt was a bit tortured this year, which comes as a surprise since the rest of the east coast relished in the presence of La Niña. The winter was warm prompting an early bud burst, but a cold snap resulted in black frost covering most vineyards. Yields were drastically reduced, as spring rains came along to aid vines through the summer to verasion. Disease pressure was low thanks to a dry summer, and while quality was splendid leading up to harvest, there was not much on the vine. An overcast February and March left producers playing a bit of a guessing game at harvest. There will be some stellar wines produced and some those that will be less so, while small lots of both will be the through-line.

Recap

2021 for most of Australia was an outstanding vintage in terms of both quality and quantity. There are some regions that missed that boat, though while it may seem like complete randomness, the entrée of La Niña after a long hot drought might be the sort of condition that many of Australia’s regions desire. We can expect the 2021 harvest contributing to the excitement, access, and abundance of Australian wine within our reach here in the US.

There may not be a better time to expand your curiosity about the wines of Australia thanks to vintage 2021.

Cheers!

This post is part of an ongoing Q & A series with our growers and winemakers. The idea is for you to get to know them a bit better, as well as the country of Australia and its wine.

What is an Australian book that everyone should read?

“Anything by Tim Winton but particularly Cloudstreet; anything by Helen Garner but particularly Monkey Grip and The Spare Room.”– Fiona Donald, Seppeltsfield (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

“The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin. The most spiritual, emotionally resonant book about Oz that exists.”– Dennis Scholl, Mother Tongue (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

“Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu and Peter Carey’s Illywhacker.”– Samantha Connew, Stargazer (Coal River Valley, Tasmania)

“Vignette by Jane Lopes.”– Sierra Reed, Reed Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence by Doris Pilkington, Dirt Music and Cloudstreet by Tim Winton, Banjo Patterson’s ‘The Man From Snowy River’ (poem).”– Niki Nikolovski and Tim Byrne, Babche (Geelong, Victoria)

“I’m a bit light on here as I find very little time to read unfortunately. I took three viti/wine mags away on holiday recently and didn’t even open the cover on one!”– Mark Walpole, Fighting Gully Road (Beechworth, Victoria)

“Intoxicating, Ten Drinks that Shaped Australia by Max Allen.”– Erinn Klein, Ngeringa (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Len Evans, How to Taste Wine. Tim Winton, Cloudstreet.”– Michael Downer, Murdoch Hill (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Intoxicating, Max Allen’s latest book on the drinks history of Australia. Epic.”– Kim Chalmers, Chalmers (Heathcote, Victoria)

“Dark Emu.”– William Downie (Gippsland, Victoria)

“Fire Country by Victor Steffensen.”– Jonathan Ross, Micro Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“Eucalyptus by Murray Bail. Great story, rich and expressive. Very Australian.” – Matt Harrop, Silent Way (Macedon Ranges, Victoria)

“The Yield by Tara June Winch.”– Andy Cummins, Rasa (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

“Aoife Clifford’s Second Sight. Southern Cross Crime is hot!”– Collen Miller, Mérite (Wrattonbully, South Australia)

This post is part of an ongoing Q & A series with our growers and winemakers. The idea is for you to get to know them a bit better, as well as the country of Australia and its wine.

What’s your favorite tool in the vineyard or winery?

“I like the old wooden presses we use. The artisanal feeling you get watching the crush happen just like it has for over 150 years is magical.”– Dennis Scholl, Mother Tongue (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

“Trusty siphon hose.”– Frieda Henskens and David Rankin, Henskens Rankin (Hobart, Tasmania)

“The coffee machine.”– Samantha Connew, Stargazer (Coal River Valley, Tasmania)

“My new hand de-stemmer.”– Sierra Reed, Reed Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“Fork Lift.”– Jonathan Ross, Micro Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“Our feet, walking the rows, often.”– Niki Nikolovski and Tim Byrne, Babche (Geelong, Victoria)

“In the vineyard: a pair of secateurs. We can form the young vine into something for the long term. If you bugger it up when its young, it will never really be okay in later life. In the winery it’s probably our Mori Dinamica crusher de-stemmer. Does a beautiful job in getting fruit ready for fermentation!”– Mark Walpole, Fighting Gully Road (Beechworth, Victoria)

“Our 20 year-old Fendt tractor.”– Erinn Klein, Ngeringa (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Our Clemons under-vine knifing machine.”–Michael Downer, Murdoch Hill (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“A wine glass. Tasting the wines throughout their evolution in the winery each day is so much fun!”– Kim Chalmers, Chalmers (Heathcote, Victoria)

“The pressure cleaner, there’s nothing more satisfying than a squeaky clean winery floor. – Bart van Olphen, Chalmers (Heathcote, Victoria)

“My horse, Arch.”– William Downie (Gippsland, Victoria)

“Cultivator.” – Patrick Sullivan (Gippsland, Victoria)

“Tasting glass.” – Matt Harrop, Silent Way (Macedon Ranges, Victoria)

“Basket press.” – Andy Cummins, Rasa (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

“My secateurs—I have a pair that can flip for left-handed people that’s perfect.”– Collen Miller, Mérite (Wrattonbully, South Australia)

This post is part of an ongoing Q & A series with our growers and winemakers. The idea is for you to get to know them a bit better, as well as the country of Australia and its wine.

How do you celebrate the end of harvest?

“More sparkling wine!”

– Frieda Henskens and David Rankin, Henskens Rankin (Hobart, Tasmania)

“Preferably with a long lunch at Fico in Hobart.”

– Samantha Connew, Stargazer (Coal River Valley, Tasmania)

“These days I celebrate the end of harvest more chill, usually a nice bottle of champagne and then maybe a detox.”

– Sierra Reed, Reed Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“Shower Beer.”

– Jonathan Ross, Micro Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“Time off and a meal out.”

– Niki Nikolovski and Tim Byrne, Babche (Geelong, Victoria)

“Normally try and catch up at a local restaurant with staff and share some great examples of the varieties we have made during the vintage.”

– Mark Walpole, Fighting Gully Road (Beechworth, Victoria)

“A long lunch or dinner with the whole team before everyone heads in their own direction.”

– Erinn Klein, Ngeringa (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Long lunch with plenty of good wines.”

– Michael Downer, Murdoch Hill (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Our harvest is really long because we work with 50 different grape varieties across two regions with different climates, starting in mid-January and usually not finished until early May, so by the end of all that usually we just hide out and rest at the end of harvest.”

– Kim Chalmers & Bart van Olphen, Chalmers (Heathcote, Victoria)

“Cold beer.”

– William Downie (Gippsland, Victoria)

“A holiday.” – Patrick Sullivan (Gippsland, Victoria)

“Party time!!! Big meal, lots of vino and laughs. Reflect, talk shit, relax. Pass out.”

– Matt Harrop, Silent Way (Macedon Ranges, Victoria)

“Dinner at Casa Carboni – easily the best restaurant in the Barossa and a walk from my house.”

– Andy Cummins, Rasa (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

“We rest and take things at a leisurely pace.”

– Collen Miller, Mérite (Wrattonbully, South Australia)

Since the famous Bordeaux classification of 1855, the Tokaj vineyard classification of 1730, and perhaps even earlier, there’s always been a desire to classify wine. It makes sense. Wine is a subject dense with all types of information that can contribute to how we feel about it – reputation, labor practices, viticulture, personalities, soil types, vinification methods, region, price, taste, etc. – and the average consumer has little context to digest all this information, nor the ability to taste a wine before it is purchased. So we rely on critics, certifications, and classifications to compile this information into a meaningful form. To help us understand what we should be spending our money and attention on, and why.

The Langton’s Classification was born in 1990, created by Australia’s premier wine auction house, Langton’s. Over the years, the Langton’s Classification has played a pivotal role in nurturing and promoting the fine wine scene in Australia. From an outsider’s perspective, Australia has frequently been a self-deprecating society. This plays out well in creating fun-loving, down-to-earth, and humble people. But it can play out poorly when it comes time to cultivate luxury industries and command the prices that fine artisanal products deserve. Counteracting this impulse, Langton’s Classification has been instrumental in the creation of Australian pride for its fine wine.

In 1990, there were just 34 wines in the classification. Langton’s most recent classification, its 7th edition released in September 2018, has awarded 136 wines. The wines are divided into three tiers:

- Exceptional: “The most highly sought after and prized first-growth type Australian wine on the market.” (22 wines on Classification VII)

- Outstanding: “Benchmark quality wines with a very strong market following.” (46 wines on Classification VII)

- Excellent: “High performing wines of exquisite quality with solid volume of demand.” (68 wines on Classification VII)

The classification has been able to chronicle trends over the years. Some things seem to never change (the staying power of red wine), while others have evolved (a move toward regionality and single vineyard wines). But always, the classification points to the wines that have had the most influence on the fine wine scene in Australia. If you want to understand the greatest wines of the country, this is the place to start.

Entry into the classification is based on a wine’s reputation and track record at auction. Wines must have a minimum 10 years of production as well as a record on the secondary market. In Langton’s own words, “Eligibility rests on how well a wine performs in an open market – the volume of demand it attracts and the prices it realises. Ultimately, the reputation of a wine is based on its auction pedigree – the record it builds up, over time.”

It’s easy to feel like classifications shouldn’t be based on price – the logic being that not all expensive wines are better – but we find that it’s actually more egalitarian to do it this way; it’s not about the individual taste of a few critics, it’s about the collective judgement of a nation when making their buying decisions. Langton’s recognizes this advantage too: “the authority of the Classification derives from its independence; the fundamental criteria for inclusion are objective and market-driven.”

Happy 30th anniversary to Langton’s and a big thank you for showing the world (and Australia itself) that the wines of this country are infinitely worthy of investment.

This post is part of an ongoing Q & A series with our growers and winemakers. The idea is for you to get to know them a bit better, as well as the country of Australia and its wine.

What’s a traditional mid harvest meal?

“Club or ribbon sandwiches (no crusts).”– Frieda Henskens and David Rankin, Henskens Rankin (Hobart, Tasmania)

“A sanga on the run from Pigeon Whole Bakery in Hobart.”– Samantha Connew, Stargazer (Coal River Valley, Tasmania)

“Usually a spicy curry or a meat pie.”– Sierra Reed, Reed Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“Riesling must-cured ceviche.When it (the riesling) comes in.”– Jonathan Ross, Micro Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“Napoli pasta from scratch.”– Niki Nikolovski and Tim Byrne, Babche (Geelong, Victoria)

“Salad rolls! (Followed by Bridge Road Pale Ale at the end of the day.)”– Mark Walpole, Fighting Gully Road (Beechworth, Victoria)

“A good lasagne.”– Erinn Klein, Ngeringa (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Toasties on the run.”– Michael Downer, Murdoch Hill (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Pasta Genovese with a caprese salad. There is always plenty of basil and loads of home-grown tomatoes in the garden.” – Kim Chalmers & Bart van Olphen, Chalmers (Heathcote, Victoria)

“Slow barbecued lamb shoulder with whatever is growing in the garden.”– William Downie (Gippsland, Victoria)

“Roast chicken and farm salad.” – Patrick Sullivan (Gippsland, Victoria)

“Not much, sandwich for lunch, something quick and easy for dinner. Meat. Salad. Wine. Back to work.” – Matt Harrop, Silent Way (Macedon Ranges, Victoria)

“Beer & schnitty.”– Andy Cummins, Rasa (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

“Lamb. We have an abundance of it in our region.”– Collen Miller, Mérite (Wrattonbully, South Australia)

This post is part of an ongoing Q & A series with our growers and winemakers. The idea is for you to get to know them a bit better, as well as the country of Australia and its wine.

What’s your favorite part about harvest?

“When the fruit is safely in the cool store.”– Frieda Henskens and David Rankin, Henskens Rankin (Hobart, Tasmania)

“The anticipation at the beginning!”– Samantha Connew, Stargazer (Coal River Valley, Tasmania)

“My favorite part about harvest is walking the vineyards and seeing the evolution of the fruit turn into wine on the vine.”– Sierra Reed, Reed Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“The energy, the people, the loud music, the beers, and drinking fermentation.”– Jonathan Ross, Micro Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“It is the culmination of the year’s work. Capturing what we have crafted in the vineyard. Essentially all the work is done when the grapes enter the winery. Our job there is to capture and ‘enhance’ what we have achieved in the vineyard and not cocking it up!”– Mark Walpole, Fighting Gully Road (Beechworth, Victoria)

“The festive feel and hanging out with our diverse crew, usually made up of many internationals.”– Erinn Klein, Ngeringa (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Beer o’clock.”– Michael Downer, Murdoch Hill (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Flavour tasting in the vineyard. Making the right picking decision is such a critical part of making wine. It’s great to walk through the vineyard and taste everything, you get such a great sense of the how the season is shaping up.” – Kim Chalmers, Chalmers (Heathcote, Victoria)

“ The adrenalin rush of the first grapes coming in.” – Bart van Olphen, Chalmers (Heathcote, Victoria)

“Lunch.” – William Downie (Gippsland, Victoria)

“Late evenings with great wine and friends.” – Patrick Sullivan (Gippsland, Victoria)

“All of it. Beer at the end of the day (or in the middle of the day) digging red fermenters, tasting young wines, it’s a great time of the year.” – Matt Harrop, Silent Way (Macedon Ranges, Victoria)

“Chats with mates about what you and they are up to. Days picking fruit together.”– Andy Cummins, Rasa (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

“Seeing quality grapes in the bin.”– Collen Miller, Mérite (Wrattonbully, South Australia)

This post is part of an ongoing Q & A series with our growers and winemakers. The idea is for you to get to know them a bit better, as well as the country of Australia and its wine.

How do you celebrate the beginning of harvest?

“Sparkling wine.”– Frieda Henskens and David Rankin, Henskens Rankin (Hobart, Tasmania)

“By stocking up the freezer with meals and ensuring I’ve got enough Explorer socks to get me through.” – Samantha Connew, Stargazer (Coal River Valley, Tasmania)

“I usually celebrate the beginning of harvest by looking at some of the greatest examples of wine from all over the world that are of the same variety as I’m making.”– Sierra Reed, Reed Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“Cleaning the press.”– Jonathan Ross, Micro Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“We don’t really. Anxiety!”– Mark Walpole, Fighting Gully Road (Beechworth, Victoria)

“Champagne and Oysters.”– Erinn Klein, Ngeringa (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Usually with a review of the previous year’s work.”– Michael Downer, Murdoch Hill (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Usually a get together with some great food and to try some of our back catalogue of wines with the newly arrived vintage staff as an introduction to Chalmers, and of course a few beers in the sun!” – Kim Chalmers & Bart van Olphen, Chalmers (Heathcote, Victoria)

“Cold beer.” – William Downie (Gippsland, Victoria)

“Chardonnay and plenty of good energy.” – Patrick Sullivan (Gippsland, Victoria)

“Picking the grapes, looking at the weather. Nothing too extreme…save that for the finish.” – Matt Harrop, Silent Way (Macedon Ranges, Victoria)

“Get anxious then start picking grapes.” – Andy Cummins, Rasa (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

“For my first harvest I received the traditional initiation. I put on the big rubber overalls and was told to get into the open fermentation vat. The waders will protect you I was told, it isn’t that deep. They lied. I had grapes in every place you can imagine.”– Dennis Scholl, Mother Tongue (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

This post is part of an ongoing Q & A series with our growers and winemakers. The idea is for you to get to know them a bit better, as well as the country of Australia and its wine.

What is the most special and unique thing about your little part of the world?

“We have this wonderful mineral rich volcanic soil, climate perfectly suited to Pinot and Chardonnay with climate change making the climate even better.”– Patrick Sullivan (Gippsland, Victoria)

“It’s very Australian, but not at all Australian at the same time.”– William Downie (Gippsland, Victoria)

“The geology in Heathcote for sure. Started out under the sea floor, add three interlaced fault lines, a few volcanic eruptions, some tectonic movements and you have a very unique terroir pedigree conveniently oriented north-south for perfect easterly aspect grape growing.”– Kim Chalmers, Chalmers (Heathcote, Victoria)

“Macedon is a cold place..the coldest winegrowing region on the mainland (couple of places in Tassie are cooler). That’s important here in Australia, that big orange ball in the sky is our limiting factor…we cop an awful lot of sun here. Our elevation, and latitude (about 37th) combine so nicely…we ripen past the heat of February, so can harvest at good potential alcohols and nice acidities. And fresh bright flavours, I call it an even ripening, no shrivel, no dehydrated flavours, (or especially in Pinot) no dehydrated aromatics. And we’re only an hour from Melbourne, so easy access to great food, music, culture, sport etc.”– Matt Harrop, Silent Way (Macedon Ranges, Victoria)

“A day of harvesting and making wine, followed by a swim in the sea, makes working on the coast special.”– Sierra Reed, Reed Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“It’s not mine! I don’t have a vineyard, or a winery. I rent space. It’s a good thing ultimately: some big things to strive for!”– Jonathan Ross, Micro Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“The Beechworth region is an elevated wine region in amongst others based in valleys or on the plains. Unique granitic and Ordovician mudstone soils, cool climate and European tree-lined roads.”– Mark Walpole, Fighting Gully Road (Beechworth, Victoria)

“The old vineyards in the Barossa are very cool. I also love the region’s crazy ability to grow high acid whites in Eden Valley and ripen Rhône varieties on the valley floor.”– Andy Cummins, RASA (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

“We have the best of both worlds: a truly rural setting living on a mixed farm with vines, mixed market garden, olive grove, fruit trees, cows, sheep… Yet are only 30 minutes away from Adelaide city that has all else we could possibly desire.”– Erinn Klein, Ngeringa (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“The Adelaide Hills, is such a diverse region. Part of the Mt Lofty ranges formed many millions of years ago we see ancient soils, elevation with a high diurnal shift keeping things fresh along with the moderate rainfall in the region.”– Michael Downer, Murdoch Hill (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Every day you drive around a corner and the landscape takes your breath away; we are extremely fortunate to live in a place of extraordinary beauty.”– Samantha Connew, Stargazer (Coal River Valley, Tasmania)

“Unique flora, fauna & low population in an island state with 40,000+ years of human continuous habitation.”– Frieda Henskens, Henskens Rankin (Hobart, Tasmania)

This post is part of an ongoing Q & A series with our growers and winemakers. The idea is for you to get to know them a bit better, as well as the country of Australia and its wine.

What grape do you think we’ll see more of coming out of Australia in the next decade?

“Pinot Noir and Italian Varieties en mass.”– Patrick Sullivan (Gippsland, Victoria)

“Pinot Noir!”– William Downie (Gippsland, Victoria)

“Hard for me to say. Although we see alternate varieties being planted and sold as wines, there is still a hell of a lot of Shiraz, Cabernet, etc. being planted. Maybe Nebbiolo, Fiano, Grüner Veltliner?”– Andy Cummins, RASA (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

“Nero d’Avola is making some big waves, a variety we introduced in 2000 and now being taken up in loads of regions.”– Kim Chalmers & Bart van Olphen, Chalmers (Heathcote, Victoria)

“Nerello Mascalese, hopefully!”– Samantha Connew, Stargazer (Coal River Valley, Tasmania)

“From warmer places, Grenache. It’s perfectly suited to our old soils and high temperatures. When farmed well and made sensitively, it’s a lovely drink. And Gamay…there’s some very good Gamay about, from young vines…keep an eye on Gamay.”– Matt Harrop, Silent Way (Macedon Ranges, Victoria)

“I think you will see more Nebbiolo coming out of Australia.”– Sierra Reed, Reed Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“More Italian varieties, and more experimentation with other grapes native to warm, dry climates. More Iberian grapes for sure.”– Jonathan Ross, Micro Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“Without doubt Sangiovese from the cooler areas; and Grenache from warmer (but there are heaps of others including Nebbiolo and Nero d’Avola). Hopefully I will have Australia’s first Petit Arvine and Cornalin in a couple of years-time, but won’t be breaking any production records for a long time!– Mark Walpole, Fighting Gully Road (Beechworth, Victoria)

“Gamay, Aligote and Aglianico.”– Erinn Klein, Ngeringa (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“More quality Merlot. Australia is not homogenous so there’s no reason it can’t make great Merlot if we plant the right clone in the right place.”– Colleen Miller, Mérite (Wrattonbully, South Australia)

“Chardonnay, just keeps coming and delivering an outstanding diverse range from around the country.”– Michael Downer, Murdoch Hill (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

When I first moved to Australia, I kept hearing the name come up: Len Evans. Passed around in hushed excitement, the name arose again and again. Other words surrounded the name: Tutorial. Scholar. And some of the most heralded wineries of the world were said in the same breath. My curiosity piqued: who was this Len Evans, and what was his cherished tutorial?

Len was a true renaissance man: working as a duck farmer, golf instructor, auto muffler producer, and script writer before finding his love for wine. He then became one of Australia’s most prominent restaurateurs, retailers, commentators, writers, and vignerons. He had his hand in nearly every aspect of the wine trade. He was larger than life, the ultimate host, and mentor to many of the current leaders of Australia’s wine industry.⠀

Len’s “Theory of Capacity” was infamous, detailing how many bottles one had left to drink in their lifetime, and how to not squander such opportunity. “You’ve got to make the most of the time you’ve got left. You’ve got to calculate your future capacity. A bottle of wine a day is 365 bottles a year…People who say you can’t drink good stuff all the time are fools. You must drink good stuff all the time. Every bottle of inferior wine you drink is like smashing a superior bottle against a wall: the pleasure is lost forever. You can’t get that bottle back.”

When Len was in his 70s, with some extra time on his hands, he came up with the idea of starting a tutorial. “The idea was to seek out, each year, twelve gifted palates who could further be trained as show judges.”

Show judging is serious business in Australia. There are dozens of different shows across the country each year, with tens of thousands of wines submitted. I won’t do a few run-down of the system here, but Huon Hooke wrote a great article for the Real Review in 2018 that details the how the wine-show system works, for those curious. But bottom line: it is an important part of wine culture in Australia.

So the Len Evans Tutorial was born. Each year, hundreds of candidates apply to have a seat at the tutorial: a week-long wine-tasting crash course. The pool of applicants includes winemakers, sommeliers, retailers, distributors and importers, educators, and wine writers—basically anyone in the trade, as well as the infrequent enthusiast who wants to try their hand at show judging.

A mix of fun and grueling is what past attendees call the tutorial. Hundreds of wines are tasted in various brackets and flights across four and a half days. But these aren’t wines you come across every day. The list of wines tasted across previous seminars is a literal who’s-who of the greatest wines in Australia and in the world: Best’s, Bindi, Bonneau du Martray, Brokenwood, Clape, Clonakilla, Coche Dury, Cullen, de Vogüé, d’Yquem, Egon Müller, Giaconda, Grosset, Guigal, Haut-Brion, Jamet, Keller, Krug, Lafite Rothschild, Leflaive, Leroy, Margaux, Mount Mary, Mouton Rothschild, Palmer, Penfolds, Philipponnat, Ponsot, PYCM, Raveneau, Rousseau, Salon, Sassicaia, Seppeltsfield, Taylor Fladgate, Trimbach, Tyrrell’s, Wendouree…the list goes on and on. And every year, the tutorial finishes with a Domaine de la Romanée Conti flight (donated by the domaine itself), specifically comparing the various grand crus that the infamous producer makes in a single vintage. Scholars are asked to determine which vineyard is which, and what vintage is being presented.

Each year, a “Dux” is crowned – the person who performed the best across the week. The wines are served blind, but the main goal isn’t to be able to nail what each wine is. The goal is to be able to assess them aptly in the context of how one might approach a wine in a wine show. How many points would this wine receive, and why? The Dux receives a round-trip ticket to Europe (business class!), to continue their studies of the great wines of the world, with a guaranteed visited to DRC.

Samantha Connew, veteran Aussie winemaker and owner of Coal River Valley’s Stargazer Wine, said this of her time at the Tutorial, in its second season: “From my perspective, the Tutorial was one of the most intimidating, inspiring, challenging, collegiate, educative weeks of my life. To be surrounded by people whose only goal was to either educate or be educated about the great wines of the world with the intention of both creating future wine judges but more importantly future great palates fed directly into my own philosophy of ‘paying it forward’ as a legacy. And part of that is being on the other side of it and being involved as an infrequent tutor and also behind the scenes of contributing to making it all happen.”

Kavita Faiella, who was a tutorial scholar in 2017, said of the week: “It was certainly the greatest wine week of my life. What I enjoyed tasting most was actually the very old Australian wines, as these are even more rare than iconic European wines, given that Australia doesn’t have a very good record for cellaring much at all, they are few and far between and so so good when you get to see one.”

This year was supposed to be the 20th year of the Len Evans Tutorial, and was the first time the tutorial was cancelled since its inception, due to COVID-19. But the industry is excited to celebrate the tutorial’s 20th year in 2021 and looking forward to a long and prosperous continuation of the tradition. This phenomenal program has benefited the Australian wine industry for the past 20 years, creating wine professionals who not only know the ins and outs of the Australian show judging system, but truly understand the benchmark wines of the world, and are invested in scholarship and bettering the community.

This post is part of an ongoing Q & A series with our growers and winemakers. The idea is for you to get to know them a bit better, as well as the country of Australia and its wine.

Viticulture Wise, what’s the biggest challenge for you?

“Our cool climate region provides many challenges that vary year to year, the biggest being frost.”– Colleen Miller, Mérite (Wrattonbully, South Australia)

“Variability in seasons, from extremely dry and warm to cold and heavy rain events, bringing opposite challenges.– Michael Downer, Murdoch Hill (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Our site is extremely windy. This strips moisture away from the leaves and fruit, so keeping enough water up to the vines and trying to avoid sunburn is always number one.”– Mark Walpole, Fighting Gully Road (Beechworth, Victoria)

“Managing vine stress in the hotter, drier years.”– Erinn Klein, Ngeringa (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“Sun. Exposure of our fruit to the sun. We work hard to achieve dappled light, especially on our north-facing sites. And moisture retention. Mulch is very important to us.”– Matt Harrop, Silent Way (Macedon Ranges, Victoria)

“Trying to get growers to consider organic practices. Then heat and water (or lack thereof).” – Andy Cummins, Rasa

“It’s taken me a few years to realise it, but every vineyard task takes three times longer than you think it is going to take.”– Samantha Connew, Stargazer (Coal River Valley, Tasmania)

“Fucking grape vines. And the fact it rains A LOT here.” -William Downie (Gippsland, Victoria)

“Undervine management. We have a strong focus on soil health and vine balance in our viticulture, which means we steer clear of any applications that can damage precious microflora or techniques that disrupt soil structure. Getting the balance right between managing weed intrusions, minimizing irrigation requirement and maintaining a gentle approach is delicate.” – Kim Chalmers & Bart van Olphen, Chalmers

This post is part of an ongoing Q & A series with our growers and winemakers. The idea is for you to get to know them a bit better, as well as the country of Australia and its wine.

Over the years, what wines have informed your winemaking efforts?

“A variety of small, mostly organic and biodynamic Champagne grower-producers: Francoise Bedel (esp. Cuvée Robert Winer), Champagne Eric Rodez (Les Crayères & Empreinte de Terroir), René Geoffroy, Roger Pouillon…” – Frieda Henskens and David Rankin, Henskens Rankin (Hobart, Tasmania)

“Pierre Marie Chermette’s Fleurie: Beaujolais influences every red wine I make. An array of German rieslings influence my winemaking, but I wouldn’t say just one producer or style.” – Sierra Reed, Reed Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“The wines that have left their greatest mark on me were ones prior to my jaunt into production. I work towards the aromatics of Monier Perreol or Maxime Magnon, but am influenced by people more: Mac Forbes, Sierra Reed, Fred Merwarth, Richard and Carla Rza Betts, for example.” –Jonathan Ross, Micro Wines (Geelong, Victoria)

“Syrah – Pierre Gaillard, Clape, Chave, Graillot. I’ve done a number of visits to the Northern Rhône. My style – barrel size, whole bunch, etc. – has been influenced by them. Tempranillo – Ribera del Duero, as opposed to the Rioja style. Keeping it pure. Visits to Vega Sicilia, Alion, Pesquera. Sangiovese – Isole e Olena Cepparello and Fontodi Flaccianello. Many visits over the years. Again pure indigenous varieties. Chardonnay – no particular producer, but stylistically Meursault-like.” – Mark Walpole, Fighting Gully Road (Beechworth, Victoria)

“The wines of Tuscany and Piedmont for the savory flavour profile and the layers of structure.”– Erinn Klein, Ngeringa (Adelaide Hills, South Australia)

“For us, it wasn’t a wine that inspired us, but a belief that there were reasons we could make a better wine.” – Colleen Miller, Mérite (Wrattonbully, South Australia)

“Where to start? So many wines and winemaking styles have had an impact on how I think about what I do, but I guess more specifically with where I have ended up probably German Rieslings (singling out JJ Prum), Chablis (Raveneau, Dauvissat, Droin) and Beaujolais (Foillard, Descombes, Thivin).” – Samantha Connew, Stargazer (Coal River Valley, Tasmania)

“So many…wine for me is first and foremost a sensual experience…so it has to taste good…..put it in me belly!!!! Small producers, farming beautifully….my earliest wine memory (of importance) is talking with Michael Brajkovich at Kumeu River, circa 1988, I’m 18 years old, and working my first vintage up the road at Nobilos. Tasting barrels, tripping at the intensity and diversity of aromas and flavours… he says ‘winemaking is mostly about knowing when to do nothing’. I’ve never forgotten that. Ever.” – Matt Harrop, Silent Way (Macedon Ranges, Victoria)

“Single vineyard German rieslings I discovered when studying in the Pfalz opened my eyes to the personality that comes from the site in great wines.” – Bart van Olphen, Chalmers (Heathcote, Victoria)

“I’m influenced by a wide range of wines and winemaking styles, notable favourites include; Vouette et Sorbee Champagne. Tour du Bon Mourvedre based wines from Bandol. Radikon, Gravner, Castellada et al. Oxidative whites from Oslavia. Gonon Syrah. Mostly however the wines from around Banyuls/Collioure as they use really similar varieties and are made in a minimal, rustic & honest way. Matassa, Bruno Duchene and the like. Locally, Tom Shobbrook’s wines are a regular go to and his Giallo, in particular, deserves an honorable mention!” – Andy Cummins, Rasa (Barossa Valley, South Australia)

“So many! a short sample would include Wendouree, Cullen, Bass Phillip, Rousseau, Jayer, Overnoy, Courtois, Lapierre” – William Downie (Gippsland, Victoria)

Jane Lopes, October 2 2020

The words we use to describe things have always made a deep impact on the way we perceive them. We see this most acutely in the description of the underrepresented and “othered” groups in society. From something as simple as calling adult women “girls” to the vast (and ever-changing) intracacies of our evolving consciousness of the LGBTQQIP2SAA community (yes, that’s a real acronym). Not only do these words affect our own perception, but they can have a vast impact on societal perception, even going as far as to effect bullying, equity, and legislation.

So, let’s talk about the words we use to describe the first Australians and their descendants. This has been a changing target over time, as academics and social leaders have been able to more clearly and correctly define how we should think and speak about this topic. There is no one perfect answer, either, as individuals who are described will have different preferences.

(A big thank you to Common Ground and Deadly Story, where we pulled a lot of this information from. Further reading resources at the bottom.)

Aboriginal – This English term dates back to the 18th century, meaning “original inhabitants” from a Latin derivation. It is generally considered an acceptable term to use when speaking about first Australians and their descendants. However, what it doesn’t do is describe Torres Strait Islander people, who are also considered first Australians, but geographically and culturally distinct from the original inhabitants of mainland (and other islands) of Australia.

Aboriginal is an adjective, not a noun. Aboriginal should always modify a noun like “Aboriginal persons” and “Aboriginal nations”. It is also always capitalized. Same goes for Torres Strait Islander: it is tempting to leave this alone as a noun (“Torres Strait Islanders”), but it is more correct to say Torres Strait Islander people. This also relates to the term “aborigine” being outdated and considered inappropriate.

Indigenous – “Indigenous” came into usage as a way to speak about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people under one banner. Though most don’t consider it offensive, neither do people feel it should be the preferred term. In very few circumstances do we need to speak of these groups together; most of the time, we can be more specific. It is also a generic term that is used not only in Australia, but all over the world, and for people as well as animals and plants, and thus does not do justice to the specific groups of Australia. The same would be said for using the word “native”.

First Australians – “First Australians” has become a popular alternative to “indigenous,” as it at least specifically refers to the first inhabitants of what would come to be known as Australia, rather than a general term that could be applied to any country. What it doesn’t do is make any further delineations between mainland and Torres Strait Islander peoples, let alone any more specific nations or language groups. It also has been called out as problematic in some usages, because “Australia” is the modern and European naming of the land.

First Nations – Going further than “First Australians,” referencing “First Nations” acknowledges the diverse nations, communities, and language groups that composed the original inhabitants of Australia, rather than lumping them together in a homogenous group. Its critics don’t like that it is not unique to Australia, but besides that, it is widely accepted.

A Specific Nation – If you’re referring to an individual community or person, it’s best to be as specific as possible. While we might use “Aboriginal” or “First Nations” to refer to a collection of many nations or a general reference to original Australians, it can be almost disrespectful to call an individual person Aboriginal. The reason being, it negates the different identities and cultures of the original nations (over 500 of them!). It’s the equivalent of referring to someone as “Asian” instead of the specific country that they’re from. In a post we made earlier this week speaking of Harold Thomas, the creator of the Aboriginal Flag, we referred to him as a “Luritja man” not as an “Aboriginal man”; we made the effort to research what nation he is from and identifies with, and acknowledged the individual identity of that nation.

Mob/Clan/Tribe – Mob is a slang term that is gaining in popularity to unite and identify an Aboriginal person with their family, clan, nation, or the larger Aboriginal community. In general, this is a term that should be reserved for Aboriginal people to use, not something we should be claiming or defining.

A clan is also referred to as a language group; there can be several different language groups within a single nation. Though the term clan is fairly commonly used, it is considered less than ideal by some scholars and groups, as it can give the wrong impression of the social structure of First Nations. Tribe is also a less preferred term, and one with colonial connotations rather than ones of nation and community.

When in doubt, stick to: Nations, Language Groups, Communities.

Further reading:

https://www.commonground.org.au/learn/aboriginal-or-indigenous

Jane Lopes, August 20 2020

A “pub” in Australia has a bit of different vibe than the word intones for the rest of the world. If you went to an Irish or British pub in Manhattan, you could expect an easy-going bar, with mediocre to decent beer selections, pretty average spirit selections, and zero chance of getting a decent glass or bottle of wine. No one goes to these establishments with the explicit goal of getting a great meal: “pub fare” is served, but its purpose is more as a sponge for alcohol than any sort of interesting culinary experience. I know this is wildly unfair to some American “pubs,” but by and large, this holds true. Otherwise, you are getting into the “gastro pub” territory, which is essentially a great restaurant that tries to give off the vibe of a bar.

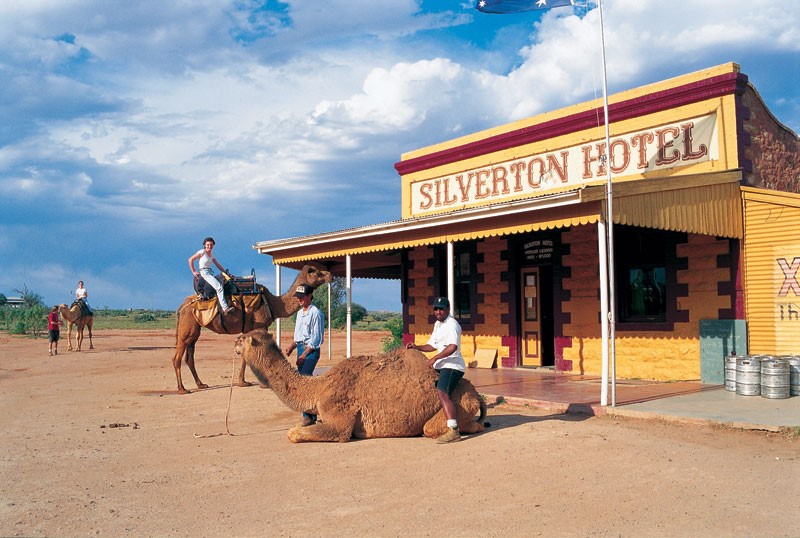

Neither definition quite fits the mold of the Australian country pub. A pub, of course, denotes a “public house” and is an establishment licensed to serve alcohol. Pubs are also often referred to as “hotels”. Historically, pubs had to offer accommodation to receive a liquor license, but those laws changed in the 1960s, and many of the urban ones have since dropped the accommodation part of their business, but not the moniker “hotel”. Many of the country pubs still do offer a few rooms for guests to stay in, but it’s rarely the focus of the busines.

So if Aussie pubs aren’t quite dive bars, aren’t quite “gastro pubs”, and aren’t quite hotels, then what exactly are they?

The identity of the country pub is, to us, defined by distinctive character, commitment to quality, and honest hospitality. A “tavern” is probably what we would call this style of bar in the United States. The trappings are usually not elaborate or trendy, but neither is this just a place to grab a cheap beer. Even in far reaches of the country, pub owners take great pride in creating a unique presentation of their region and hospitality.

Take, for example, the Wandi Pub. The Wandi Pub is based in Wandiligong, where it takes its name from, in the Alpine Valleys of northeast Victoria. Marked by a vintage “Mountain View Hotel” sign and decorated with multicolored pennant banners and beer signs, the Wandi Pub presents a humble front. Inside, you’re faced with not only one of the best food, wine, and beer lists in the region, but a genuine sense of warmth and hospitality. The Wandi Pub is also a community center: families and friends meet over a few beers, kids celebrate birthdays, strangers face off against each other in billards competitions, and live music takes the stage. They even offer a “luxury charter” (aka a big comfy van) that can be hired to take you to the ski hills or a winery.

The Wandi Pub is one of our favorites, but there are dozens (probably hundreds!) more examples of this kind of Aussie pub: original, hospitable, and delicious. There’s the Silverton Hotel in western New South Wales. It’s the start and end of many an adventuring trail, and many movies have been shot there, including Priscilla Queen of the Desert and Mission Impossible II.

Speaking of “Priscilla”, there’s a beer-chugging pig with that name at a great Tasmanian pub called Pub in the Paddock. Priscilla can drink a (heavily diluted) can of beer in seven seconds! Pub in the Paddock is located in Pyengana, a village in northeastern Tassie known for its delicious cheddar cheese. The pub itself is known for its locally-driven food, warm service, and, of course, Priscilla.

The list goes on and on…They aren’t always (actually rarely are they) on-trend, formal, or elaborate. They’re all about simplicity, a genuine expression of region, and creating community. And through these ideals, country pubs have founded and maintained the idea of what hospitality looks like in Australia.

Jane Lopes, August 7 2020

Hi Americans, you might be mispronouncing these Aussie wine words. How do we know? Because we did, over and over again, until we figured it out. In the wine world, we put a lot of credence into pronouncing regional and foreign words correctly. That doesn’t mean you need to say “Vosne Romanée” in a French accent, but it should probably sound something like “Vone Ro-mah-nay” not “Vos-nee Ro-man-ee”. With wine words in the same language as ours, there seems to be an assumption that we know the deal, but this is often not the case. (Also, if you think Australians speak the same language as Americans, please refer to our first post in this series…)

So here for your consideration, 5 Australian wine terms (mainly regions, with one grape) that Americans naturally emphasize differently than Australians do.

Barossa Valley

Most Americans tend to say Bar-OH-ssa Valley. The emphasis stays on the same syllable, but the “OH” becomes an “AH” for the Australian pronunciation. It’s the difference between the “o” sound in Otis (OH) and otter (AH).

Yarra Valley

We Americans have the tendency to make this a soft “a” – a la the “a” sound in car, far, or bar. The Australians harden it up a bit – think about rhyming with Yogi Berra, or the “a” sound in care, bear, wear, etc. This also informs your pronunciation of Shiraz. It’s shir-AZ, not shir-AHZ.

Geelong

This one is intimidating! We’ve heard everything from GEE-long (with a hard “g”, like the beginning of geese), to JEE-long (with the correct softening of the “g” but with the emphasis on the first syllable). The trick is to emphasize the LONG, with the first syllable being “jhe” like the beginning of “just”. Rhymes with “duh” 😊

Heathcote

The trick here is to emphasize the “HEATH” (which is pronounced just like the candy bar), and to shorten the second syllable. Also, think more “cut” than “coat”.

Semillon

This is a controversial one. We here at LEGEND stick to the French pronunciation of Semillon (SEM-ee-yon), but if you want to fit in in the Hunter Valley, you’ll want to pronounce those L’s! We couldn’t find a good recording for this one, but it goes like SEM-eh-lon. Kind of like the end of Avalon or Babylon.

These are the biggest offenders, in our opinion. Some of the scariest sounding regions are actually some of the most phonetic! If you follow your instincts for Manjimup, Porongurup, and Nagambie, you’ll probably get it right.

Jane Lopes, July 29 2020

Australia has always been at the forefront of technological innovations in the wine world. From precision viticulture to weather monitoring, partial root drying to regulated deficit irrigation, Australia has been one of the modern pioneers of using technology to streamline viticulture and winemaking. This approach can be embraced – with the outlook that technology is providing the information and means to make better and more sustainable wine – or, it can be met with disdain – with the feeling that technology moves us further from an honest connection with the land and grapes.

Whichever way you feel, it’s hard to deny the importance of technology in accumulating data with which to approach global warming, which threatens to have a serious effect on the wine industry. We’ve already seen the impact of global warming in wine legislation across the world, as Bordeaux votes to approve adding grapes like touriga nacional and petit manseng to its approved AOP varieties, Tuscany plants Saperavi, and Champagne reverts to some of its less fashionable historic grapes. Australia is trying to get ahead of the necessary accommodations, and as such, Wine Australia has just completed a three year study with the University of Tasmania, resulting in a comprehensive report titled Australia’s Wine Future: A Climate Atlas.

The data from this report is based largely on computer modeling projections, with fancy sounding (and scientifically advanced) tools like direct and indirect aerosol feedbacks, gravity wave drag, and cloud microphysics. The result of this technology and effort is a 487-page full report that not only presents a summary of climate trends over the past decade, but projections of future climate change and options for adapting to and managing climate variability. We applaud this groundbreaking report, and hope that it will lead to Australia protecting its wine regions in the face of climate change, and other regions undertaking similar initiatives.

A few of our highlights:

- A calendar that links the main stages of budburst, flowering, veraison and harvest to the weather and climate risks that occur at specific stages

- Breaking down regions by general climate zones and analyzing relative threats: “Hot Wet” (Hunter Valley), “Hot Arid” (Riverland), “Warm Dry” (Grampians), “Mild Dry” (Margaret River), and “Cold Wet” (Tasmania).

- Climate Analogue Tool to identify analogous regions around the world, based on temperature, precipitation, evaporation, humidity, and radiation. This tool could be utilized to share adaptation methods globally, as well as identify appropriate grapes and viticultural techniques for different regions.

- Climate projections of increased temperatures, increased aridity, and more severe heatwaves across Australia, and sooner than previously anticipated. Each region is approached individually, with detailed assessments.

We recommend that you check out the whole thing. We’ll be back with some more detailed breakdowns, but this is a must-skim for anyone studying Australian wine and/or climate change.

Jonathan Ross, July 21, 2020

Before we begin to bring the wines and produce of Australia to the US, we must start at the point at which we’ve been shown to start.

The Welcome to Country or Acknowledgment of Country will open many gatherings and events in Australia. A Welcome to Country is perhaps one of humanity’s oldest traditions, and is a formal ceremony that has existed among Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nations for many millennia. Its purpose is to welcome those from other nations or clans onto one’s own land; before Europeans colonized Australia, there were over 500 of these First Nations. The Welcome to Country is a sign of hospitality and respect for people and the land they care for. Traditionally, and still today, the Welcome to Country is a ceremony that occurs between the First Nations. No one other than a member of a First Nation could Welcome a group of people to that Country.

When non-indigenous people hold a meeting or event, inviting a Clan or Nation Elder to conduct a Welcome to Country ceremony is increasingly common. There is no treaty between the First Nations of Australia and the non-indigenous people that now largely inhabit the island, and while this does not replace a treaty, it both pays respect to and amplifies the recognition of the original custodians of the land.

An Acknowledgment of Country is a way that all people can show respect and awareness for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture and heritage, and the ongoing relationship the traditional custodians have with their land. As with the Welcome to Country, it precedes an activity and recognizes the specific First Nation where that activity is being held, and the people of it.

Our Acknowledgment of Country is a bit different. We are not meeting in Australia. We are not even holding a meeting. But our business is built on the importation and wholesale of Australian wine; produce grown from the earth and transformed into wine.

Wine creates one of the greatest connections between humans and the earth, between us and mother nature. It is that connection compelled Aboriginal and Torres Straight Island people to be custodians, not owners, of their land.

As we, LEGEND Imports, bring the bounty of Australia to the US, we recognize the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of the First Nations of Australia as the original custodians of the land, and that this land has neither been ceded, nor has treaty been established with those that occupy the land. We pay respect to the Elders of these Nations both past and present.

We recognize the Jaara People of the Dja Dja Wrung Nation whose country produces the wines we import under the origin name of Heathcote.

We recognize the Wathaurong people of the Wathaurong Nation whose country produces the wines we import under the origin name of Geelong.

We recognize the Boonerwrung people of the Boonerwrung Nation whose country produces the wines we import under the origin name of Gippsland

We recognize the Taunergong people of the Taunergong Nation whose country produces the wines we import under the origin name of Beechworth.

We recognize the Wurundjeri people of the Woiwurrung Nation whose country produces the wines we import under the origin name of Macedon Ranges.

We Recognize the Kaurna People of the Kaurna Nation whose country produces the wines we import under the origin names Adelaide Hills and Barossa.

We recognize the Ngarrindjeri People of the Ngarrindjeri Nation whose country produces the wines we import under the origin name of Wrattonbully.

We Recognize the Laimairrener People of the Laimairrener Nation, the Pyemmairrener People of the Pyemmairrener Nation, and the Paredareme People of the Paredarerme whose countries produce the wines we import under the origin name of Tasmania.

As our portfolio grows to support more wines from further reaches across Australia, we will continue to recognize the original custodians of the lands from which those wines come.

Follow the links below to learn more about the over 500 Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander First Nations of Australia.

Jane Lopes, July 11, 2020

My first insight on Aussie nicknames was communicated by my initial sublet hosts when I moved to Australia in February of 2017. Wendy and Ben, as their email addresses announced, signed their notes to me “Wen and Benny”. The total number of syllables did not change, yet they both had a nickname to either shorten or lengthen their given names. And that’s how I learned the #1 rule of Aussie slang: there’s always a nickname.

Having a nickname is a sign of familiarity and affection in Australia. Most of the time this involves shortening a name: Tasmania becomes Tassie, Chardonnay becomes Chardy, Riesling becomes Riz. Garry becomes Gazza or Gaz (don’t ask us why), Michael is Mickey (same number of syllables, but certainly more familiar and casual), and Phillipa becomes Pip. When a name can’t be shortened, the only option is to lengthen it. My colleagues at work started calling me “Jane-O” a few months in; my husband Jon got “JR”. Sometimes the nickname doesn’t correspond to your own name at all; other colleagues at work got names like “Beard”, “Froth”, and “Frenchie”. It’s all in good fun, with an aim to make people feel the love.

Other slang is not necessarily a nickname, just an alternate word. Australian words have a bit more levity to them, and are always fun to say. “Yakka” means “work”, most often used in the phrase “hard yakka” to denote a strenuous job. Candies and sweets are called “lollies” and if you’re really exhausted, you might say you’re “buggered”. It’s hard to take yourself too seriously when you’re “so buggered out from the day’s hard yakka that you just need a handful of lollies!”

Idioms, though, is where the real fun starts. I remember coming to Australia and hearing full sentences where I had no idea what the meaning was. I suppose every culture has these, but Australia seems to be ahead of the crowd in terms of slightly absurd sayings. “She’ll be right, mate” is one of my favorites, and essentially means “It’s going to be okay, friend.” The first time I heard this, I asked “who is she?” to which my friend just shrugged. “Sweet as” really gets me too. It basically means “Sweet as hell” or “very sweet” but nothing comes after the “as”. “This wine is sweet as” would be a full sentence!

Though we may not be able to travel to Australia right now, we can let language help us feel a bit closer. Choose some of the following to work into your daily repertoire!

Arvo = Afternoon

Boot = Car trunk

Bottle-O = Liquor shop

Brekky = Breakfast

Budgie Smuggler = Speedo

Chockers = Very full, “chock full”

Chook = Chicken

Chrissie = Christmas

Daggy = Uncool

“Fair dinkum!?” = “For real!?” (and one can reply with “Fair Dinkum!” – “Yes, for real!”)

Footy – Australian Rules Football. VERY popular. Everyone “has a team”.

“F*ck me dead” = Something like “well, I’ll be”, demonstrating an element of surprise

“Good on ya” = “Good job”

“I reckon” = Something like “I imagine” or “I think” or “I suppose”

Maccas = McDonald’s (Australia is the only place in the world where McDonald’s has an official alternate name that is used on buildings and branding.)

Mozzie = Mosquito

Pash = Kiss (verb or noun)

Pissed = Drunk

Pot, Pony, Schooner, Seven, Middy, Butcher, Bobbie, Pint = Different sizes of tap beer servings (varies by state).

Root = Sex (usually said as “have a root”)

Sickie = Sick day (Australians get 20 paid ones each year, mandated by the federal government!)

Skull = To down a beer

Tomato Sauce = Ketchup

“Save it for Ron” = “Save it for later on.”

Snag = Sausage

Sausage Sizzle = Every Sunday, in every Bunning’s parking lot (Bunning’s is a Home Depot equivalent), a $1 slice of white bread with a Snag and Tomato Sauce for Charity.

Stubby = Small bottle of beer

Stubby holder = Polystyrene beer koozie

Ta = Thank you. Australians still use “thanks” and “thank you” but “ta” is often used as a little follow up or a more casual sentiment.

Tall poppy syndrome = The tendency to disparage or take down prominent and successful people

Tradie = Tradesman, i.e. construction worker, plumber, electrician, sanitation worker, truckdriver, carpenter, etc.

“Wanna hoot on my missus?” = “You can take a sip of mine.”